- From the Director

- How Successful Countries Tackled Stunting

- Hunger for the Holidays

- Raising the Federal Minimum Wage: Have We Reached the Tipping Point?

From the Director

Rarely if ever do most of the world’s 7.8 billion people agree on something, but “2020 has been the hardest year I can remember” may earn that distinction.

Yet without minimizing the ongoing pain and suffering that intensified when the COVID-19 pandemic began early this year—the very harsh conditions of daily life for far too many people, the 1.5 million lives lost, and the serious problems facing the global population as a whole—I am glad to report, in this final issue of Institute Insights for 2020, that there are glimmers of hope for people facing hunger.

On December 9, the World Food Programme (WFP) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Norwegian Nobel Committee chairwoman Berit Reiss-Andersen said that with the 2020 award, the committee wanted to “turn the eyes of the world to the millions of people who suffer from or face the threat of hunger.” This prestigious award offers a much-needed boost to public awareness, particularly in rich countries, of the humanitarian disaster that continues to unfold.

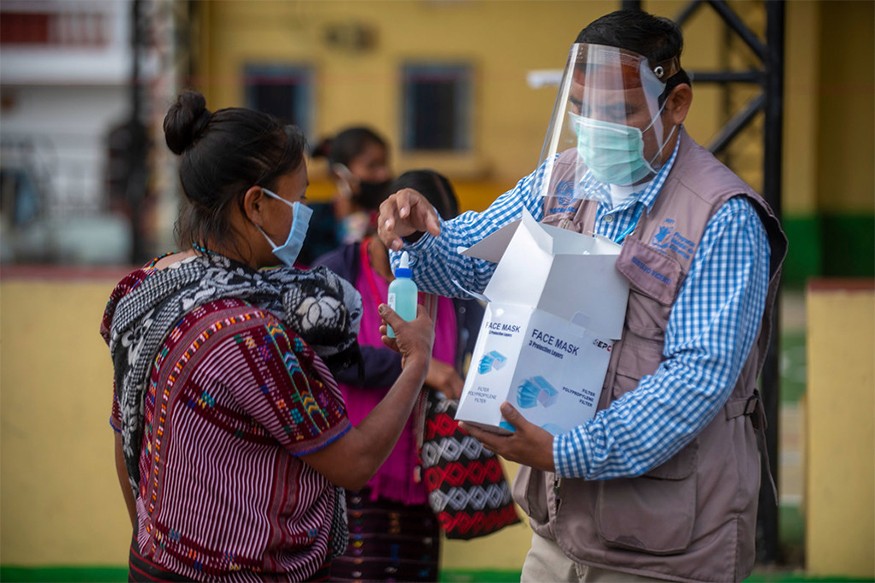

Institute Insights has reported throughout the year that nutrition experts warned of a looming malnutrition pandemic as the virus spread rapidly and many countries shut down much of their public life in an effort to contain it. They projected that an additional 10,000 young children would die every month due to a combination of the global economic crisis caused by the virus, and people’s inability to travel to seek health care, food, and other essentials. People who are already malnourished, particularly children, are most vulnerable to the impacts of disrupted food supplies, closure of maternal/health nutrition programs, interruption of essential health care such as vaccination against childhood diseases, and other unintended consequences of public health restrictions.

Still, there have been significant funding shortfalls for humanitarian assistance efforts, as many donor countries also had severe economic disruptions and hospitals full of COVID-19 patients. Bread for the World continues to join many other advocates and humanitarian organizations in calling for additional assistance to enable low-income countries to prevent or respond to the malnutrition pandemic.

Qu Dongyu, director-general of sister agency the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), said of the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize, “This prize is a new engine driving the food security issue to the forefront, underlining the importance of international solidarity and multilateral cooperation.”

Another sign of hope in early December was the U.S. Congress’s passage of the bipartisan Global Nutrition Resolution, H.Res.189, after faithful work since early 2019 by Bread for the World advocates. The resolution supports “sustained United States leadership” in making faster progress against global maternal and child malnutrition, and it supports the U.S. Agency for International Development’s “commitment to global nutrition through its multi-sectoral nutrition strategy.”

Passing a bipartisan resolution on nutrition in both the Senate and the House in a year such as 2020 is a major achievement. It took the persistent efforts of Bread for the World activists, who began building support for the resolution in early 2019. Just one example of what I mean by “persistent efforts”: Bread activists held nearly 600 meetings with their members of Congress to explain the need for the resolution and win cosponsors.

It is this kind of persistence and dedication that will be required to lift up the hunger crisis at home and abroad so that our elected officials respond to the call to action exemplified by the Nobel Prize.

I wish you and your families all the very best for the holiday season.

Merry Christmas and here’s to a peaceful and healthy 2021!

Asma Lateef is director of Bread for the World Institute.

How Successful Countries Tackled Stunting

By Tanuja Rastogi, ScD

A global nutrition revolution began in 2008 when the Lancet medical journal alerted the world to the devastating and lifelong consequences of child malnutrition. In this landmark report on maternal and child nutrition, comprehensive research by leading health experts showed how poor nutrition during the 1,000-day window from pregnancy to age 2 leads to irreversible damages in physical and cognitive development.

Tragically, stunted children are more likely to die before the age of 5 than well-nourished children. Those who survive are unable to reach their full potentials. Despite progress since 1990, when 40 percent of the world’s children were affected by stunting, there are still far too many stunted children—an estimated 144 million, more than 20 percent of all children.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated the way forward on reducing stunting. Research just released by Standing Together for Nutrition projects that unless more resources are made available soon, an additional 2.3 million children will become stunted due to the pandemic’s impact on nutrition, and by 2022, about 9.3 million additional children will be affected by wasting, which is a life-threatening condition. The dilemma is that the global economic and financial crisis makes it more difficult for governments—donors and countries with limited resources alike—to maintain funding for nutrition.

Nonetheless, the knowledge and understanding that child malnutrition damages a country’s “human capital” and hinders its efforts to achieve economic prosperity has propelled the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) global movement over the past decade, and advocates remain engaged. Today, more than 60 nations have joined SUN—committing to tackle all forms of malnutrition through a whole of government approach and multi-sectoral actions. The World Health Organization has called for a 40 percent reduction in global stunting levels by 2025, and the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include ending all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

But what was less clear in 2008 was how to make significant reductions in stunting among large groups of people. In some countries, stunting affected more than half of all children. Experts said that scaling up proven nutrition “interventions” or actions, which are implemented primarily through the health sector, would achieve a reduction of only 20 percent. They advised that substantial additional progress would be possible only if countries made other key sectors “nutrition sensitive.” Particularly important sectors included agriculture, food, and social protection systems.

In 2020, we can look at how some countries succeeded in doing this. New “Stunting Exemplars” research, supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, sheds light on how countries can significantly reduce stunting and identifies a path for progress. A consortium of researchers looked in depth at five countries that achieved rapid reductions in their stunting rates, relative to their economic growth rates, over a period of about 15 years. Taking economic growth into account was important because stunting and poverty are interconnected, but it often takes decades for countries to make significant progress against poverty. The five countries are Peru, the Kyrgyz Republic, Nepal, Senegal, and Ethiopia.

The researchers worked carefully and thoroughly to understand what these countries did right and identify the big drivers of change. Their findings, published in September 2020 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, affirmed the Lancet’s earlier assessment that there is no single solution.

The authors emphasize that “one size does not fit all” because they found that the five countries adopted different mixes of solutions to achieve their long-term improvements. It proved essential to identify the right mix of interventions and approaches by clearly diagnosing the strengths and weaknesses of each context. Also critical to success was a focus on scaling up or expanding the actions that proved most effective. Both ingredients rely on having good data, so strong data collection and analysis systems are a third necessary factor.

Researchers found that it was essential to have a mix of direct nutrition actions and nutrition-sensitive efforts, with efforts by both the health system and other systems. It is not surprising that delivering services at scale—reaching all who needed them—was critical. As expected, direct nutrition interventions delivered through health systems were required for success—including maternal nutrition, adequate maternal and newborn medical care, and support for breastfeeding. Other health actions were also necessary, including making family planning resources available and preventing pregnancy among adolescents. The non-health sector measures that proved most important were reducing poverty, improving food security, supporting education for girls, reducing gender disparities, and providing access to clean water and hygienic living conditions.

The Stunting Exemplars research also showed that countries can reduce stunting dramatically, but patience is important since progress may take 10 to 15 years. The Exemplar countries began their campaigns before the publication of the Lancet report in 2008. The plans were not designed specifically to reduce stunting. Rather, they focused on filling in the gaps in essential community services. What did vulnerable mothers, children, and communities need, but did not have, as they were seeking not only to survive but to improve their nutritional status and their productivity?

The finding that strengthening a nation’s human capital through nutrition is likely to take 10 years or longer is important: it enables nutrition advocates to be prepared to frame reducing stunting as a longer-term effort when they communicate with their governments and the public. Realistic expectations may help sustain longer-term political commitment and longer-term investments. Telling the story of how women who are stunted are more likely to have children who become stunted, for example, can help people understand why it is important to ensure that adolescent girls are well nourished: it will pay off in the longer term.

The findings of the Stunting Exemplars research also explain Bread for the World’s continued advocacy for bipartisan support on child nutrition. Making lasting progress will take more than one presidential term. As mentioned in this issue’s Letter from the Director, in early December, both chambers of Congress passed a global child nutrition resolution, with bipartisan leadership from Sens. Chris Coons (D-DE) and Susan Collins (R-ME) and Reps. Jim McGovern (D-MA) and Roger Marshall (R-KS). The resolution is a welcome example of the U.S. commitment to ending child malnutrition, a commitment that will prove crucial in the decade to come.

Tanuja Rastogi, ScD, is senior global nutrition policy advisor with Bread for the World Institute.

Hunger for the Holidays

By Michele Learner

In the United States in December 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the economy are the main topics, sometimes almost the only topics, of our public discourse.

When the pandemic began, food insecurity and hunger in the United States skyrocketed, particularly among children. In the first several months, Congress enacted several COVID relief bills. Bread for the World members advocated steadfastly for the legislation to include adequate funding for nutrition programs, as well as for policy improvements to help ensure that everyone has enough to eat. For example, while schools are closed, funding for school meal programs may legally be used instead to augment household grocery budgets. This enables families to replace the meals their children are no longer getting at school.

Hunger has surged again this fall. COVID-19 cases rose sharply, and some states imposed tighter restrictions in an effort to slow the transmission of the virus, save lives, and avoid overwhelming hospitals. Funding from earlier relief measures had largely run out by September, and a new COVID-19 recovery bill has been stalled in Congress for months.

Analysts say it is likely that there is more hunger in the United States now, at the end of 2020, than at any time since at least 1998, when detailed record-keeping began. Previously, the Census Bureau had not collected specific information on whether households were able to get enough food.

According to Census Bureau survey data collected in late October and early November 2020, one in eight adults in the United States, and one in six adults in households where children lived, reported that, in the past seven days, they “sometimes” or “often” did not have enough food to eat. Structural racism pervades our society, and hunger during the pandemic is no exception—the same survey data showed that 22 percent of people in Black households reported going hungry in the previous week, nearly twice the rate of all American adults.

Some signs of socioeconomic distress are hard to miss, such as the hundreds of cars lined up at food distribution sites. Others are hidden, such as significant increases in reports of domestic violence. Still others are trends that we might not have thought of but make sense—for example, many more instances of shoplifting, and what experts call a distinctive shift in the types of items being stolen: staples such as bread, pasta, and baby formula.

Widespread hunger is completely unnecessary in a wealthy country such as the United States, and it is unconscionable. It is the responsibility of the U.S. government, which collects taxes and decides how to spend tax revenue, to ensure that people who cannot afford to buy enough food do not go hungry. As was true before the pandemic, most people who participate in nutrition programs fall into the broad categories of children, elders, people with disabilities, and people who have lost their jobs.

Coming up next in this issue, my colleague Todd Post considers a long overdue and much more sustainable solution: raising the federal minimum wage.

Another longer-term solution to current problems that is often mentioned—arguably unfairly—is our next generation. Bread for the World frequently emphasizes the importance of ensuring that children get the right nutrition. We have also called for the right learning opportunities, such as quality early education for all children. Like many other adults, I feel more hopeful when I think of the world’s youngest leaders and activists—Malala, Greta Thunberg, the students of Parkland, FL, and others.

Most recently, I heard about TIME Magazine’s first-ever “Kid of the Year,” an amazing 15-year-old scientist and mentor, Chloe Gong, and her fellow honorees, all ages 8 to 16. Ian McKenna from Austin, TX, caught my attention because he is an anti-hunger activist. Now 16, he was in the third grade when he began to apply his love of gardening to the problem he saw: many of his classmates were not getting enough to eat. He persuaded his school to allow a garden on the grounds, recruited volunteers, and began to distribute vegetables to the school community. McKenna’s Giving Garden is now active in five additional schools.

McKenna has the skills of a leader—he found ways to meet the additional needs he saw (there were weekends when he cooked more than 100 meals at home) and to adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic (these included a gardening hotline, videos to help people who are beginning to grow vegetables at home, and virtual cooking classes). He reflects the spirit of Bread for the World’s grassroots activists: “Hunger doesn’t stop,” he says. “So I won’t stop until it does.”

Michele Learner is managing editor with Bread for the World Institute.

Raising the Federal Minimum Wage: Have We Reached the Tipping Point?

By Todd Post

The movement to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 started in 2012 and has been gaining momentum ever since. The 2020 election could prove to be a tipping point.

I believe that raising the minimum wage is key to progress against hunger, so I have been hoping that the idea gains bipartisan support. Florida just shone some sun on my hopes. In the November election, the majority of Florida voters cast their ballot for Amendment 2, raising the state minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2026.

In September 2021, Florida’s minimum wage will increase from $8.56 to $10 an hour, and then it will increase by $1 every year through 2026. The Florida Policy Institute estimates that Amendment 2 will lift 1.3 million households out of poverty and raise the wages of more than 25 percent of the state’s workforce.

Most states and many municipalities have set their minimum wage higher than the federal minimum wage of $7.25. Few though have approved and scheduled increases to as much as $15, and Florida is significantly more conservative than the states that have previously done so. This is what makes Amendment 2 such a big deal.

The federal minimum wage is stuck at $7.25. It hasn’t been increased since 2009. This is the longest period it has remained the same since the federal minimum wage was first established—in 1938. Every year that it remains at $7.25, inflation reduces its real value. In 2019, David Cooper of the Economic Policy Institute estimated that minimum wage jobs have lost $3,000 in purchasing power since 2009.

Full-time minimum wage work pays just a little over $15,000 a year, so $3,000 is a big deal.

Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would increase the hourly wage of more than 33 million workers. According to a national survey conducted just months before the election, most Americans support raising the minimum wage, including a majority of Republicans. Maybe they agree with me that people need a raise now more than ever.

I know that many people would say that this is not the right time to raise the minimum wage. The economy is weak. Can businesses afford it? But in fact, there is no better time, because when people have more purchasing power, they can buy more of what they need and want, which will help the economy recover more quickly.

Researchers have shown that moderate increases in the minimum wage at the state and local level do not increase unemployment or drive inflation—two of the main reasons given by policymakers who are reluctant to increase the minimum wage.

Another objection I sometimes hear is that if the minimum wage rises too quickly, companies might just replace workers with robots. But this is a greatly exaggerated concern. If automation were eliminating the jobs of manual laborers as some people claim, it would be made obvious by significant increases in productivity. This is because productivity is measured as how much work a person can do in an hour, and that figure would increase if there were fewer workers and more production assistance from robots. But as concerns about automation eliminating jobs rose over the past two decades, productivity rates have been stagnant. In any case, if large numbers of workers were displaced because of automation, we have options to resolve the problem.

I don’t want to create the false impression that persuading Congress to enact a $15 federal minimum wage will suddenly be a simple matter. President-elect Biden supports a $15 minimum wage, and policy analysts are already working to identify what he could accomplish if the final results of the elections for the Senate lead to a divided Congress where most progressive legislation has little chance of passing.

One of the improvements that the Biden administration has the power to make is to require federal contractors to pay their workers a higher minimum wage. There are about 5 million federal contract workers, according to a recent estimate, and the majority of jobs are in lower-paid sectors such as office cleaning and cafeteria work rather than in highly skilled fields such as aerospace engineering. The situation currently is that federal contracts are won on low-cost bids, meaning that contractors have an incentive to pay low wages. Requiring higher pay would make the jobs more sought after, which in turn would give private sector employers reason to raise their wage rates as well—so they can retain top-performing workers.

Starting with a group of workers whose pay is controlled by the executive branch is a high-road approach to government contracting. I would argue that this kind of approach is necessary in order to improve pay in the private sector economy, where too often, companies are free to choose to make more money by taking a low-wage, low road approach.

Todd Post is senior researcher, writer, and editor with Bread for the World Institute.