By Faustine Wabwire, Bread for the World Institute

Over the past few months, I have been part of conversations focused on what it will take the global community to reach the goals of ending hunger and poverty by 2030. If you, like many of our fellow hunger advocates, have been following closely, you’ve heard bold new proclamations such as… “It’s no longer business as usual,” “leave-no-one-behind,” “common but differentiated responsibility,” “zero hunger”… But what do all these mean?

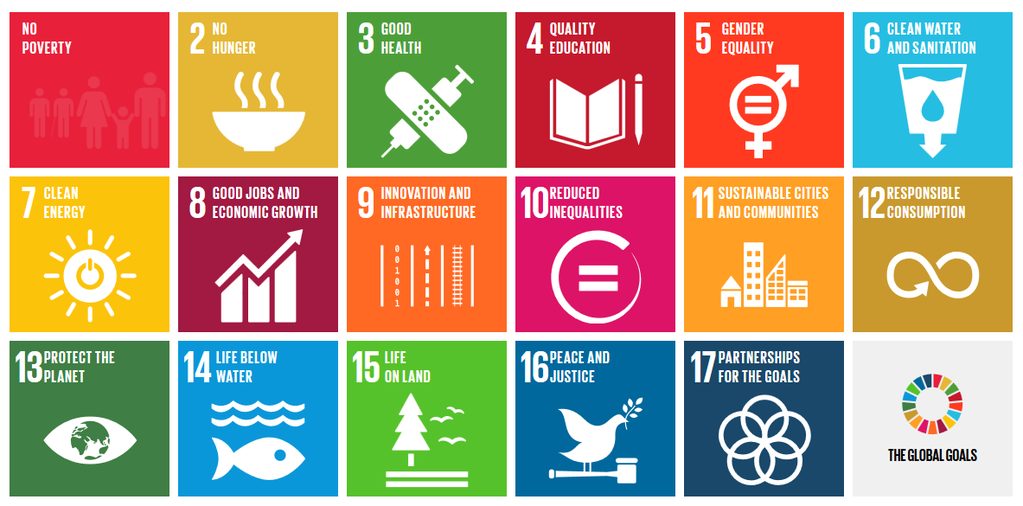

2015 is momentous in the history of global development. Last week, citizens of the world adopted a new, ambitious 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the historic Sustainable Development (SDG) summit in New York. The Agenda includes a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end hunger and poverty, fight inequality and injustice, tackle climate change, and achieve gender equality by 2030.

In the first of two addresses to the United Nations General Assembly, President Obama stated:

“America is committed to a development agenda that eradicates extreme poverty by 2030. We will do our part to help people feed themselves, power their economies, and care for their sick. If the world acts together, we can make sure that all of our children enjoy lives of opportunity and dignity.”

As the world’s attention and resources begin to focus on the means of implementing this ambitious agenda, it is clear that real work lies ahead for everyone — governments, civil society, and the private sector. And, of course, most of the progress of the past 15 years under the Millennium Development Goals is due to the hard work of hungry and poor people themselves, in every country. That must be bolstered by global, national, and political leadership.

How to fulfill the promise that our country will do its part has already been the focus of a lot of forward thinking. On September 21, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) released a statement of its long-term vision and theory of change, Extreme Possibilities: Ending Extreme Poverty by 2030. The strategy articulates the U.S. government’s pivotal role as a leader in global development.

It’s heartening that USAID is thinking in terms of extreme possibilities to end extreme poverty — and it’s timely. The World Bank’s latest projections, released this week, indicate that the proportion of people living in extreme poverty is likely to fall to under 10 percent of the global population in 2015. This is certainly an affirmation that the world can indeed end extreme poverty by 2030.

It’s great news, not least for Bread advocates, who may occasionally have wondered whether we are working more toward an ideal than toward something that will be real. But there’s no denying that complex and tough challenges remain. The goals of eradicating poverty and hunger will require major changes in the structures and, perhaps even more daunting, the social norms that allow them to persist: inequalities within and across nations, poor governance at national and global levels, weak institutional capacity, gender discrimination, and others.

According to World Bank President Jim Kim:

“This is the best story in the world today — these projections show us that we are the first generation in human history that can end extreme poverty. This new forecast of poverty falling into the single digits should give us new momentum and help us focus even more clearly on the most effective strategies to end extreme poverty. It will be extraordinarily hard, especially in a period of slower global growth, volatile financial markets, conflicts, high youth unemployment, and the growing impact of climate change. But it remains within our grasp, as long as our high aspirations are matched by country-led plans that help the still millions of people living in extreme poverty.”

So the catchphrases are literally true: in order to live up to the ambitious, universal development agenda that “leaves-no-one-behind,” it can’t be business as usual. World leaders, civil society, the private sector, and ordinary people must work together to make the needed investments, promote mutual accountability, and sustain the political will to achieve the SDGs by 2030.

Faustine Wabwire is the senior foreign assistance policy analyst at Bread for the World Institute