By Todd Post

Forward-looking nations invest in infrastructure. It is a judicious use of resources because the investment pays for itself over time. But it often has immediate benefits as well, some of them less tangible and less likely to be touted at the time. New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie argues, for example, that President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal infrastructure investments in the 1930s paid instant dividends: they rescued democracy at a time when “it was not clear democracy would survive the long night of the Depression.”

As I discussed in a piece last month, infrastructure is not limited to bridges and roads. Every country needs to invest in its human infrastructure as well. Workers drive innovation and productivity. “Building” this infrastructure takes investments during childhood, including education, as well as supports that enable people to work productively as adults.

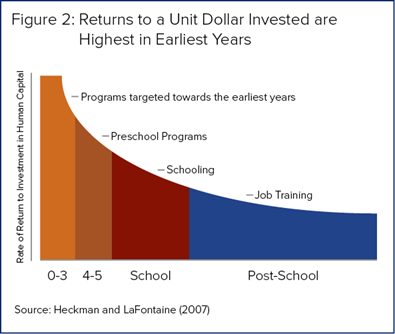

Accordingly, Bread for the World advocates that Congress and the administration prioritize investments in the 1,000 Days between pregnancy and a child’s second birthday. This is the most important period in setting the course of a person’s entire life, and supporting babies and toddlers has the highest “return on investment.” Of course, it will be many years before the infants and toddlers now in the 1,000 Days enter the workforce. It’s certainly an example of how “investing now” pays off later.

My earlier piece also mentioned the economist James Heckman, who developed the “Heckman curve” to illustrate the impact of investments at various life stages. (See the chart at top).

A 1,000 Days infrastructure includes WIC, Medicaid, child care, paid parental leave, and making permanent the recent one-year expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Here are some of the benefits a 1,000 Days infrastructure would bring, backed by evidence based on research:

Every dollar spent on pregnant women in WIC generates anywhere from $1.92 to $4.21 in Medicaid savings on the health care of newborns and their mothers. Medicaid covers nearly half of all births in the United States, and hospitalizations associated with pregnancy and childbirth are among Medicaid’s largest expenses.

Reducing the rate of low birthweight through WIC’s prenatal care programs is one source of these savings. The newborns of women who participate in WIC prenatal services have a 25 percent lower rate of low birthweight (weighing less than 5.5 pounds at birth). Even more strikingly, they have a 44 percent lower rate of very low birthweight (weighing less than 3 pounds, 5 ounces at birth). The cost of care for very low birthweight infants is 30 percent of all newborn healthcare costs.

Low-wage workers, who are more likely than others to qualify for WIC and Medicaid, are less likely to have access to paid family leave: fewer than one in 10 low-wage jobs offer it. New mothers whose jobs provide paid leave are able to stay with their newborns longer, and they are more likely to initiate, establish, and continue breastfeeding. An infant’s nutritional needs are best met with exclusive breastfeeding (no other food or water) for the first six months. In 2014, suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States was associated with nearly $20 billion in medical and nonmedical costs.

High-quality child care for low-income children generates an average of $7.30 for every dollar spent, as the children grow up healthier, do better in school, and earn more over the course of their working lives. Everyone in the country pays a price when parents can’t work because they cannot afford quality child care–particularly the higher fees for infant and toddler care. The cost to the U.S. economy is at least $57 billion annually in lost earnings, productivity, and revenue.

Similarly, estimates are that every dollar spent on expanding the Child Tax Credit will generate an average of $8 in benefits to the country as a whole. Child poverty costs the United States between $800 billion and $1.1 trillion a year. The temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit in the American Rescue Plan is projected to cut child poverty nearly in half—which is why Bread is calling for the expansion to be made permanent.

As an anti-hunger organization, Bread for the World generally focuses on nutrition during the 1,000 Days. Bread members have been working faithfully for years to draw the attention of policymakers to the importance of nutrition in the 1,000 Days. Mothers and children everywhere need sufficient food and good nutrition during the 1,000 Days. It’s true in Kenya, and it’s true in Kansas.

But as I argued in an earlier blog post, WIC alone cannot build a 1,000 Days infrastructure strong enough to meet the needs of our nation’s babies and toddlers—or the needs of our nation’s economy. Bread advocates’ efforts over several decades have helped make WIC a strong and effective program. But much of WIC’s success depends on the success of interrelated parts of a 1,000 Days infrastructure—the aforementioned Medicaid, paid parental leave, child care, and Child Tax Credit benefits. That is why Bread advocates for a complete 1,000 Days infrastructure package.

Todd Post is senior researcher, writer, and editor with Bread for the World Institute.