By Todd Post, Bread for the World Institute

The 2015 Hunger Report, When Women Flourish…We Can End Hunger, is about to become the “immediate past” edition of Bread for the World Institute’s flagship report. This coming Monday, November 23, the 2016 edition, The Nourishing Effect: Ending Hunger, Improving Health, Reducing Inequality, will become our current Hunger Report.

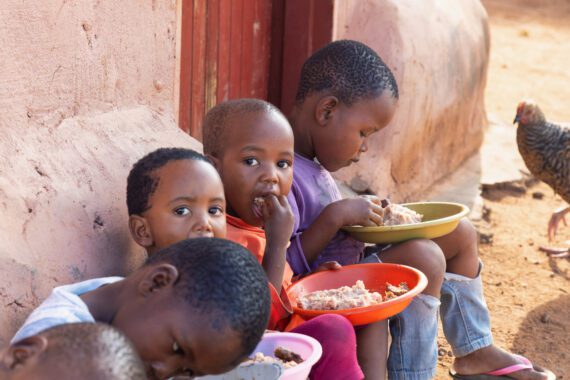

When Women Flourish… is the first Hunger Report to center directly on women’s empowerment. Earlier reports devoted significant time to gender bias, women’s rights, and the role of women in ending hunger, but the 2015 report draws a straight line linking gender inequality to hunger and poverty—and conversely, linking women’s empowerment to ending hunger. It’s one of the most popular and influential reports we’ve ever done—for example, the topic has quickly made its way into Bread’s Offering of Letters, the signature grassroots campaign of letters seeking to change policy. The 2016 Offering of Letters will seek to end preventable maternal and childhood deaths, emphasizing the preventive power of nutrition to help accomplish this goal.

In April of 2014, my Bread for the World Institute colleague and I were in Malawi on field research for When Women Flourish… We Can End Hunger. As with most of our travels in rural areas of low-income countries, we found the road conditions to be challenging and the available vehicles not always able to weather them. Our car broke down on the way to a meeting with a village women’s group. The driver managed to find a mechanic, but the meeting was delayed for a day. As it turned out, we would not have been able to conduct the meeting as planned anyway, because on the original date, one of the members of the women’s group died in childbirth. Around the world, more than 800 women die every day in childbirth.

Ninety-nine percent of all maternal deaths occur in developing countries, making maternal mortality the world’s most inequitably distributed health measure. The global rural maternal mortality rate is 2.5 times that of the urban rate. Hunger rates are higher in rural areas, and hunger and malnutrition are linked to greater risks of women dying in childbirth.

No one would mistake the United States for a developing country, but most of the American public—including elected officials—is not aware of how poorly the United States is doing on some health indicators compared to other developed countries. The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate among high-income countries, double the death rate of Canada and triple that of the United Kingdom. The United States is one of only eight countries in the world, wealthy or low-income, where maternal mortality has actually gotten worse since 1990.

The United States ranks at the bottom or near the bottom on a number of other health indicators as well. In the 2016 Hunger Report, The Nourishing Effect: Ending Hunger, Improving Health, Reducing Inequality, we argue that this is because, as a nation, we tolerate higher levels of hunger and food insecurity than people in other high-income countries will put up with. The report focuses on the relationship between hunger and health. Let me emphasize the words “reducing inequality” in the title. Without reducing inequality in health care, ending hunger and improving health will remain out of reach. “Of all forms of inequality,” said Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., “injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” King said this nearly 50 years ago. A lot has changed in the past 50 years—and a lot hasn’t. African American women are still nearly four times as likely as white women to die in childbirth or from complications of pregnancy.

The 2015 Hunger Report raises concerns and makes recommendations that are still urgent. As it joins our list of past editions, I think you’ll find a lot of continuity between the themes of “women’s empowerment” and “hunger and health.”

Todd Post is senior researcher, writer, and editor at Bread for the World Institute.