By Derek Schwabe

The Brookings Institution published an important report last month that advocates and policymakers shouldn’t miss. The Ending Rural Hunger (ERH) report is one of the first and most comprehensive pieces of research to take precise aim at rural hunger. There’s good reason to do so, since an estimated 75 percent of the world’s hungry people live in rural areas. The additional income and safety nets that are part of inclusive development are slower to reach the more remote areas of low- and middle-income countries. These communities often lack basic infrastructure, may have large numbers of people weakened by malnutrition and illness, and are more likely to adhere to rigid and deep-seated gender norms that prevent women from participating fully in their communities, economies, and societies.

One of the most impressive contributions of the ERH report is its rigorously screened and carefully curated assembly of data on rural hunger. The 106 painstakingly identified indicators are particularly valuable for policy makers since they are grouped according to three essential ‘ingredients’ for reducing rural hunger:

- Locating needs

- Prioritizing effective policies, and

- Summoning the necessary resources—financial, political, and human.

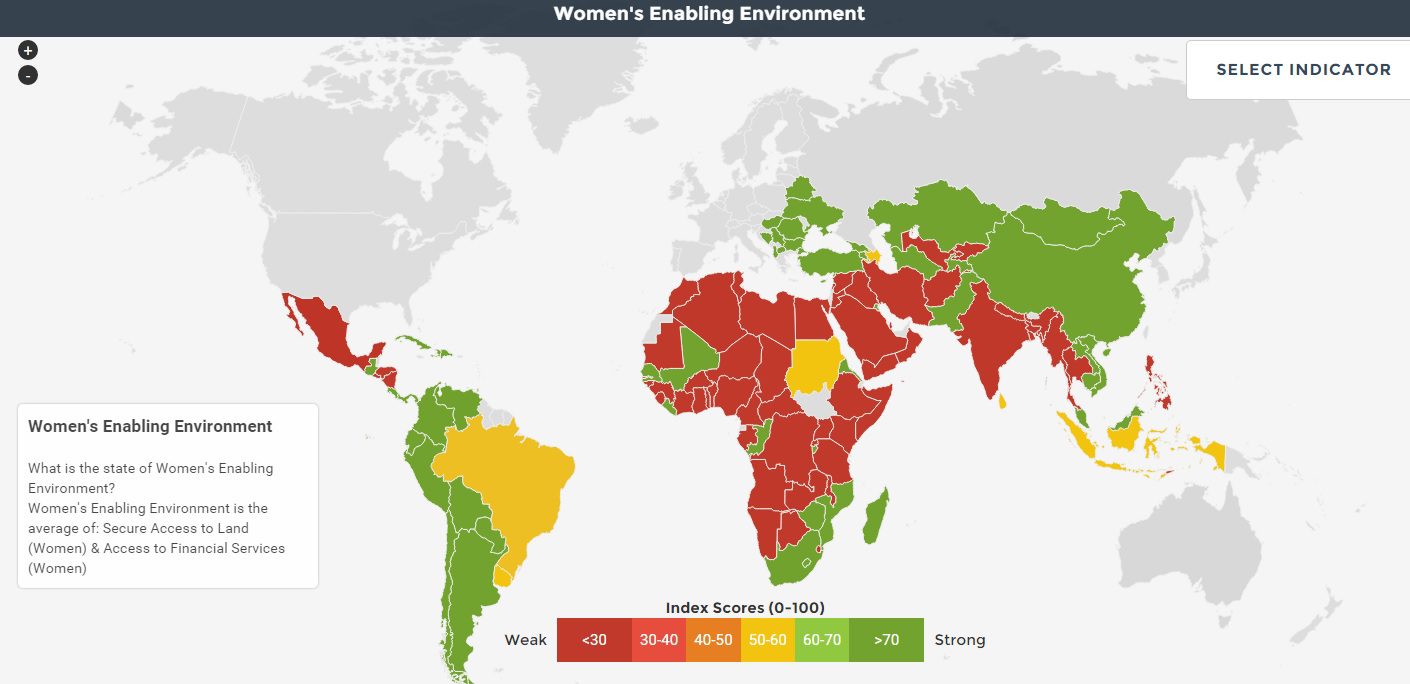

Raising the status of women is inextricably linked with making progress against hunger. About half of the reduction in child malnutrition between 1970 and 1995 is attributable to improvements for women, e.g., opening primary and secondary education to girls (2015 Hunger Report, p. 15). These factors outweighed seemingly obvious “hunger solutions” such as increasing the amount of food available. Yet as our 2015 Hunger Report’s Missing from the Picture data visualization shows, a startling 80 percent the global data needed to measure women’s status, rights, health, economic participation, and more simply does not exist. Thus it’s no surprise that only two of the ERH data tool’s 106 indicators reference women specifically – one on access to land and the other on access to financial services.

Land and credit are prerequisites for productive farming, and considering the majority of employed women in the developing world work in agriculture, these indicators are important. But again and again, we find that women and men are living in vastly different economic and social conditions. Two indicators are not enough in places where women have little bargaining power at any level of society. In addition to more subtle forms of gender bias, such as belittling stereotypes, and structural, such as unequal access to education, one in three women faces outright violence in most parts of the world. Domestic violence as well as assaults by neighbors or strangers is rampant. This affects women’s ability to work and earn enough to meet their needs and those of their families. Discrimination against women demands that data on a wide range of indicators be disaggregated by gender. The old assumption that what’s true for a male “head of household” is true for the rest of the family is simply not valid.

Considering the rigorous vetting process used to screen the data, the scarcity of gender indicators in the ERH report suggests that other indicators were either not complete enough or of too poor quality to make the cut. Even the two indicators that were included had missing data for a number of countries. This should raise a red flag—possibly a line of red flags. As the newly minted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) usher in the promise of a data revolution, data on women and girls, particularly those in rural areas, needs to be at the forefront. Without significant progress on women’s rights, the world cannot meet the SDG goal of ending hunger by 2030.

Derek Schwabe is a research associate at Bread for the World Institute.