By Michele Learner

Famine is about much more than food insecurity. It is about compounding vulnerabilities that leave millions of people without basic human dignity, without hope for the future. — Reena Ghelani, Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

In some good news for the record numbers of people currently living in famine or near-famine conditions, Congress approved a fiscal 2017 supplemental budget that includes about $1 billion in additional funding for famine relief. Bread for the World advocated persistently for these extra resources. The money will go to help people in South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and Nigeria. It will save many lives, particularly those of young children. Children under 5 are far more likely to die from malnutrition than older children and adults, which explains why, of the estimated 260,000 people who died during Somalia’s 2011 famine, more than 150,000 were young children.

Before the U.S. announcement of additional funding, the global community’s response to the 2017 appeal for famine relief funds had been very weak. Less than 25 percent of the needed emergency resources had been pledged. Money continued to arrive very slowly even after parts of South Sudan had met the official definition of famine, which includes grim criteria such as a child acute malnutrition rate of 30 percent or more. The new U.S. contribution, while far from enough to meet all the needs, will help significantly — both in itself, and in its influence motivating other donors to increase their own contributions.

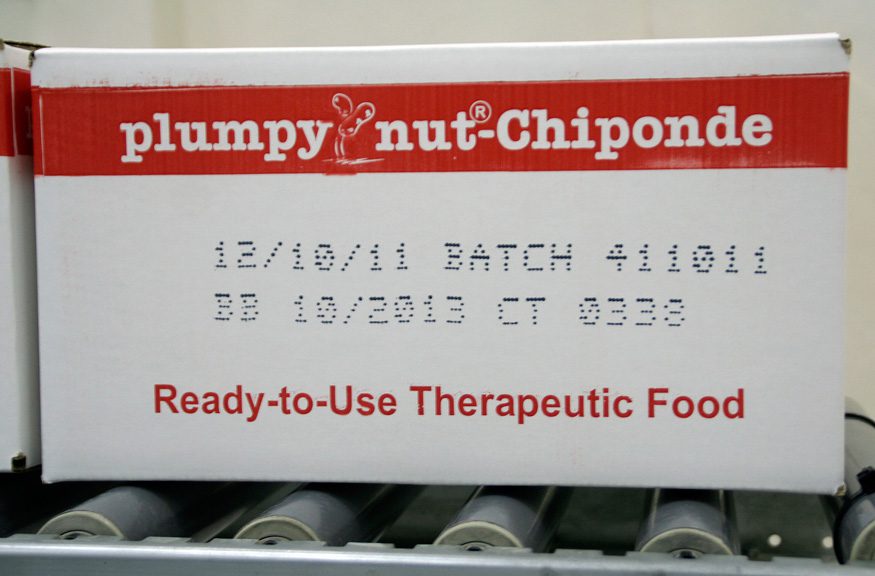

Another encouraging sign is that we know more now about which actions are most effective and should be top priorities in near-famine situations. The familiar news footage of mass distribution of sacks of grain is a less common strategy. This is both because of the high potential for violence as desperate people gather in large crowds, and because it is very difficult in such situations to ensure that the food reaches those most in need. Instead, in the frequent cases where food is available locally but people are dangerously malnourished because they don’t have money to buy it, families are given vouchers to buy food at the market. Children with acute malnutrition, particularly if it is already severe, are treated in therapeutic feeding centers. As possible when children start to recover, parents are given a supply of ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTFs) and taught how to use them.

Writing in 2012, in the aftermath of the 2011 famine in Somalia, Dina Esposito, then director of the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, recalled working as part of a disaster response team during Somalia’s 1991 famine. “We learned a lot from that famine response … and looking back I can say that we played it smarter this time around [in 2011],” she wrote. The increasing recognition that people weakened by malnutrition are more vulnerable to preventable diseases meant that more resources were allocated to health and hygiene programs, such as vaccination, clean water, and essential supplies (for example, soap).

“Much improved early warning systems [received from the experts at Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) and Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit] gave us a clear picture of both nutritional needs and market prices,” Esposito continued. Food stockpiles, including RUTFs, were pre-positioned near areas expected to have the greatest needs.

Of course, by far the best solution to famine and other hunger crises is to prevent them in the first place. The famine in South Sudan and the threatened famines in Somalia, Yemen, and Nigeria are primarily the result of conflict. According to military analysts, these conflicts have no military solutions. They drag on and on, awaiting mediation and political solutions. Conditions have also been worsened by climate change, as people fight over both shrinking supplies of water, and access to land suitable for growing food or grazing animals. The Institute’s 2017 Hunger Report, Fragile Environments, Resilient Communities, looks more closely at conflict, climate change, and other factors that make people vulnerable to hunger, and at how these types of fragility can be addressed.

Prevention also means investing in nutrition so that people are healthier and better able to withstand and recover from crises such as prolonged drought. As explained in our earlier article, “Skinny Budgets Versus Hungry Babies,” U.S. assistance for global maternal and child nutrition helps treat children with acute malnutrition, supports efforts to prevent anemia and stunting, promotes lifesaving breastfeeding practices, and meets other urgent health and nutrition needs. Yet for fiscal year 2017, the administration budgeted approximately $256 million for maternal and child nutrition. That amount — the total for all regions of the world — is less than 1 cent for every $100 in the federal budget. Strengthening this prevention and early treatment budget would prevent deaths and suffering and, incidentally, reduce the need for emergency food aid.

The need to do more is obvious. Between the 1991 and the 2011 famines in Somalia, the humanitarian relief sector made valuable progress on effective response. And yet, as Esposito recalled, “In July 2011, I remember calling [a colleague] to let her know that famine had been officially declared in Somalia. It was with an air of both sadness and disbelief that I myself absorbed the news that we had actually reached this point.”

The situation in 2017 perhaps warrants even greater sadness and disbelief, because although the countries facing famine have very different contexts and needs, the fact is that we know how to prevent and respond to such crises. The global community has not yet chosen to make available all the resources needed to avert famine, though the sums are modest in the context of donor countries’ budgets. The countries of the world have, however, committed to tackling climate change with the needed urgency; to making determined efforts to end conflicts — efforts that don’t stop until the wars do; and to taking the other actions needed to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Action. Now is the time.

Michele Learner is associate editor at Bread for the World Institute.