From his childhood on a Minnesota hog farm to studying economics in college to a Peace Corps stint in Malaysia to a long career as an economist, David Buland has explored the connections between food and efficiency for most of his life.

As part of his studies at Harvard in the 1970s, David researched hunger. He worked as a programmer, supporting other people’s projects centered on India’s water resources. He wrote his thesis using income and food consumption data from an Indian village during a time of famine. “The statistics showed that the monied people were getting the calories,” he says.

The experience inspired David to join the Peace Corps, serving the Malaysian Department of Agriculture. “In the center of the country, they were converting jungle to rubber and palm oil estates,” he remembers. “I helped start three hardware stores and also repaired tractors. I learned that Fiat tractors used the same parts as the Allis-Chalmers tractors I’d grown up with!” Malaysia was a fast-growing country at the time. “Still, there was hunger, and I witnessed it,” he says. “The hungry people were the ones without steady jobs.”

During his third year in Malaysia, Dave married a woman named Tiew-Eng. In the mid-1980s, the couple relocated to the United States to start a family. “Our first child born was born one week before I entered Wartburg Theological Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa,” David says.

At Wartburg, he joined the Public Witness Committee, where he first heard about Bread for the World—and its founder, Art Simon. “Another student said there was a Bread event happening in Dubuque, and a bunch of us went to learn more.”

With his background in economics, his faith, and having witnessed the effects of hunger on those without means, David immediately recognized the value of Bread’s model.

David realized he would make “a better economist than a pastor.” He returned to school for his master’s degree in economics and worked as an economist for the rest of his career. He retired in 2019, but soon returned to full time work with the USDA, where he helps perform cost analysis on projects like the Farm Bill, the multiyear law that governs an array of agricultural and food programs.

“Because I was working for the federal government, I can’t get involved with advocacy activities,” David says. So his involvement with Bread for the World is mainly as a donor. “Then a year ago, I was sending a donation and noticed the monthly giving option.” David began making an automatic monthly gift as a member of the Baker’s Dozen. He calls it “the most effective way I can support an end to hunger.”

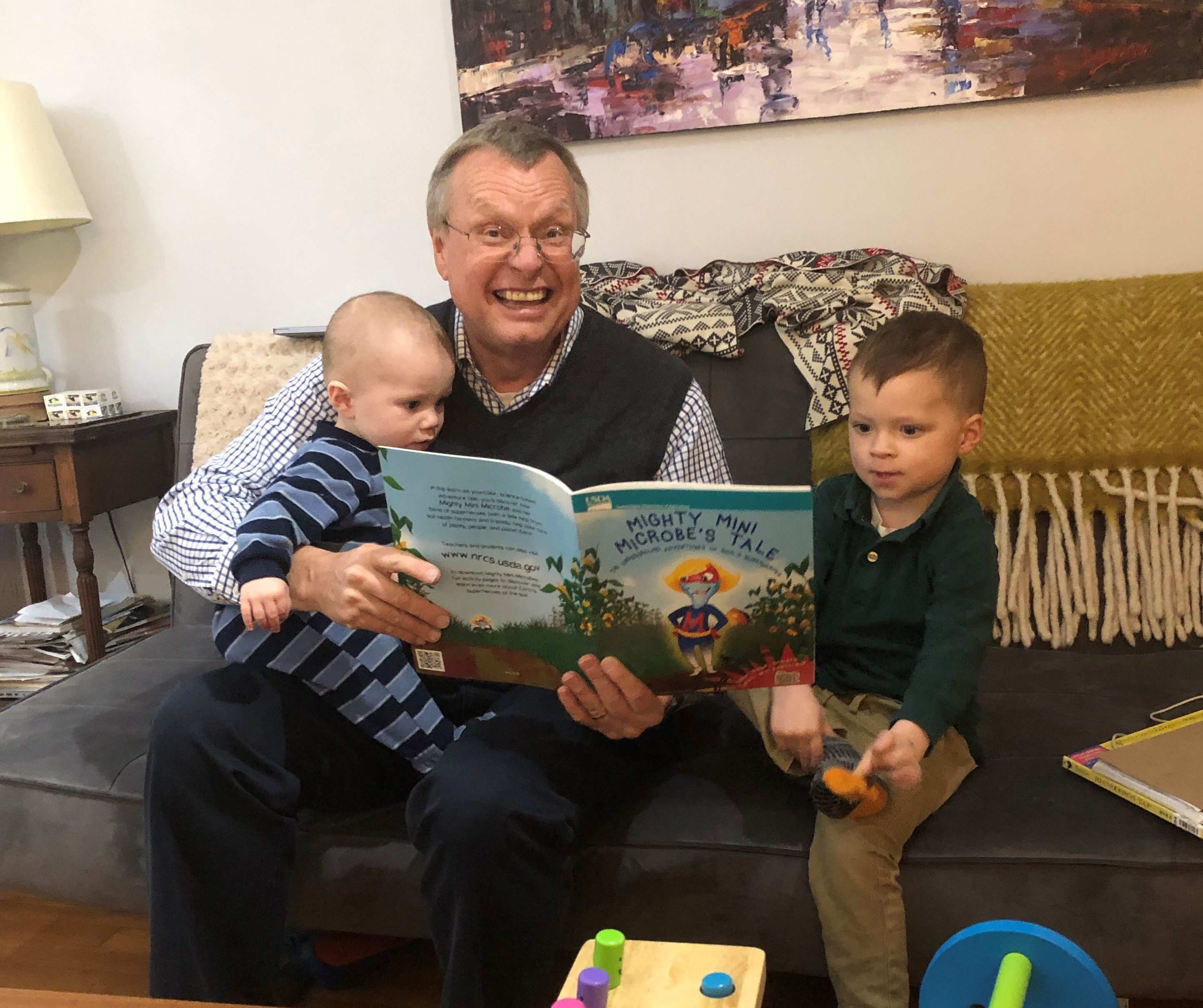

Today, David remains active in the ELCA’s North Texas Synod Public Witness. He also serves as webmaster for a USDA economist group. David and Tiew-Eng belong to Grace Lutheran Church in Fort Worth. They have two grown children and five grandkids.

“Being an economist, I see readily how much the church can accomplish—and how much more the government can do to end hunger,” David says. “Voters let Congress know what is needed. From an economist’s view, Bread for the World is the most effective way we can help.”