Over the past several decades, hunger has become less about calories and more about nutrients. While there are still far too many people who struggle to get enough calories, 3 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet, even if they spend most of their income on food. Many families in lower-income countries eat meals composed mainly of staple grains such as rice, maize, or sorghum, which may keep them from feeling hungry but do not contain all the nutrients that people—especially babies, children, and adolescents—need to lead healthy, active lives.

Food is fundamental to human life and inextricably connected with a host of other aspects of human society, from agriculture to social status. Ending hunger and malnutrition would bring transformational change to society. Yet the reverse is also true: a world without hunger calls for changes that resolve its root causes. Two of the oldest root causes and perhaps hardest to change: starting wars and marginalizing people based on identity traits like religion, gender, race, and/or national origin.

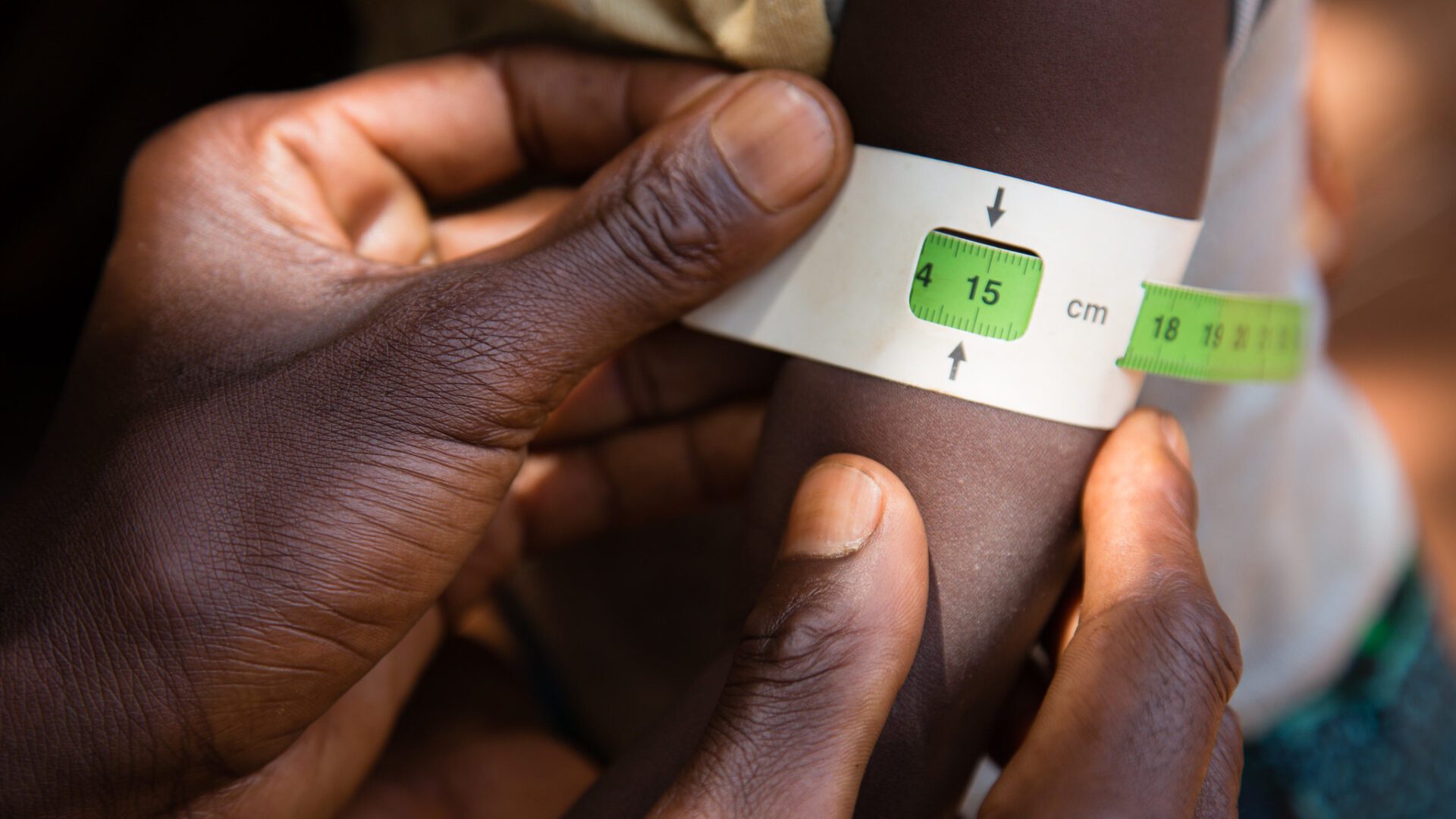

A top priority in efforts to end hunger and malnutrition is to dramatically reduce the share of young children with Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM), also known as childhood wasting. SAM is the most severe and dangerous form of childhood malnutrition, and an estimated 45 million to 50 million children under 5, more than 7 percent of all children in this age group, suffer from it.

As Bread has mentioned, the most familiar use of “wasting” in the United States is in the phrase “wasting away.” Children suffering from wasting or SAM are far too thin. They appear frail and lethargic. But a definition that ends there fails to mention the critical problem that can take children’s lives and damage the health of those who survive—their immune systems are compromised.

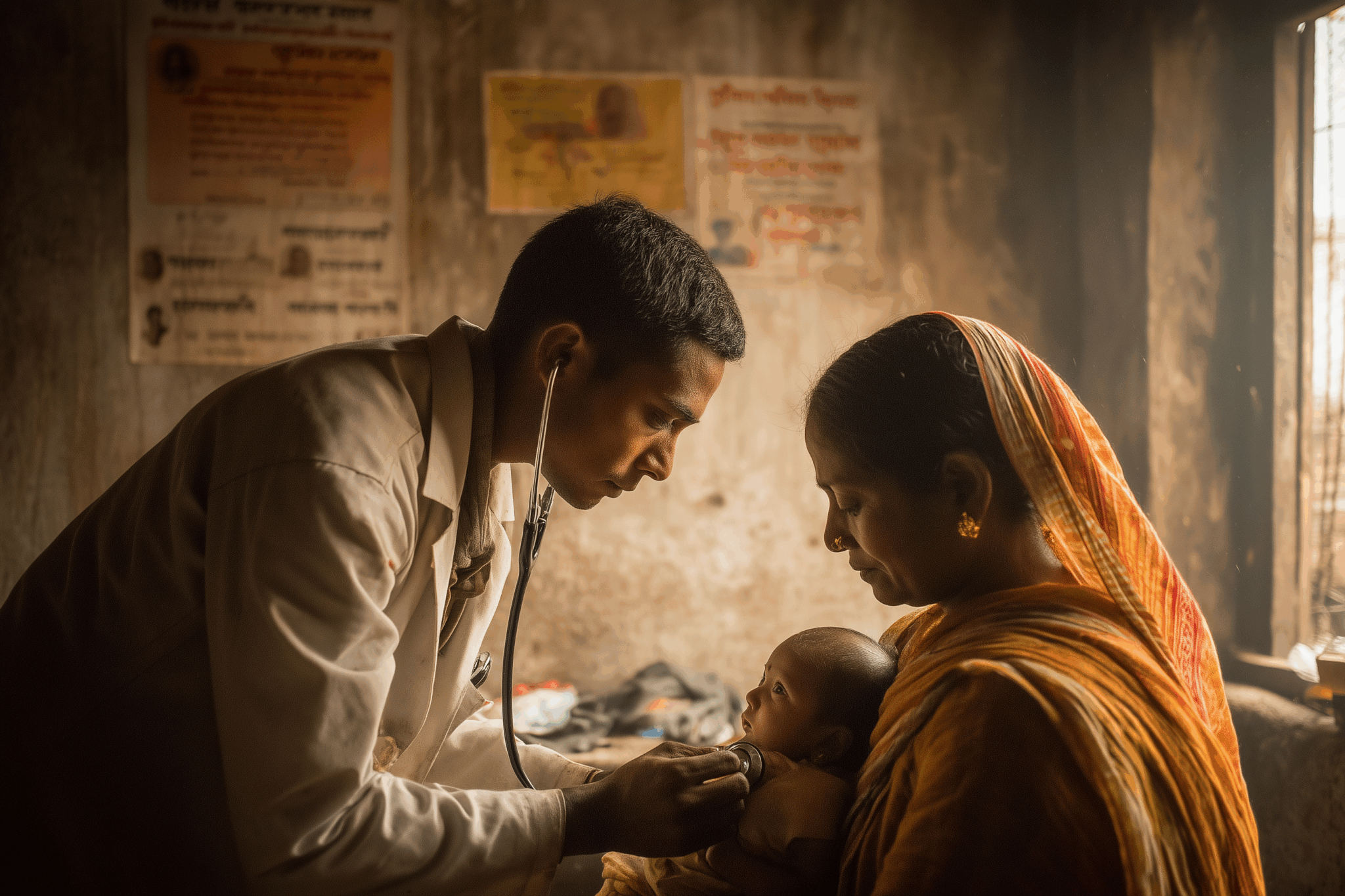

Every year, SAM causes the preventable deaths of 2 million children under 5. Frequently, they die of diseases or infections that generally are not life-threatening to healthy children. In fact, the data show that children suffering from severe wasting are up to 12 times as likely to die as well-nourished children. The International Rescue Committee said in 2023 that it is “one of the top threats to child survival” around the world.

As Bread has frequently mentioned, the United States and nearly all other countries adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. SDG 2 is to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030. The world will be unable to reach SDG 2 without an effective approach to preventing and treating childhood wasting.

The Global Action Plan on Child Wasting is part of the effort to reach SDG 2. Released in 2019, it is based on the findings of research into why little progress had been made on reducing wasting between 2015 and 2019. It set two targets: reducing the rate of childhood wasting to below 5 percent by 2025 and to below 3 percent by 2030.

The Global Action Plan established that it is vital to reduce the incidence of low birthweight through better maternal nutrition. Health providers had known for some time the importance of good nutrition during pregnancy as well as before pregnancy among adolescent girls and young women.

A research team from the Universities of California at Berkeley and San Francisco has recently learned more through a “study of studies,” meaning that the results of several studies (in this case, 33) were combined. Taken together, the studies showed that “early life malnutrition, which is associated with increased risk of disease, impaired cognition, and death, occurs earlier than expected.” This means that good nutrition during pregnancy and prior to pregnancy is even more important than previously understood.

The larger research project is the most comprehensive study to date of growth faltering among children from birth to age 2. Senior author Benjamin Arnold, PhD, MPH, of UC San Francisco, said, “The early onset of growth faltering implies a very early window for intervention, in particular the prenatal period, and potentially broader interventions that help to improve nutrition among women of child bearing age.”

Low birthweight (less than 5.5 pounds) is used as an indication that the mother may be malnourished, but it does not necessarily mean that she is. Still, it is not usually difficult to obtain this information, and tracking community trends is one way of assessing whether, and how well, efforts to improve the nutritional status of the women and girls who live there are working. It may also improve the likelihood that a mother’s later pregnancies, and/or her daughters’ pregnancies, will lead to babies who are born at a healthy weight.

Michele Learner is managing editor, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.