Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of pieces about how we can ensure that very young children have the nutrients they need to survive and grow up healthy.

One powerful motivation for Bread for the World’s work is concern for children. Our members work to ensure that all children, no matter where they were born, have access to nutritious food. This has been true throughout Bread’s history, from our campaigns for vaccination against childhood diseases in the 1970s and 1980s to our newest campaign, Nourish Our Future.

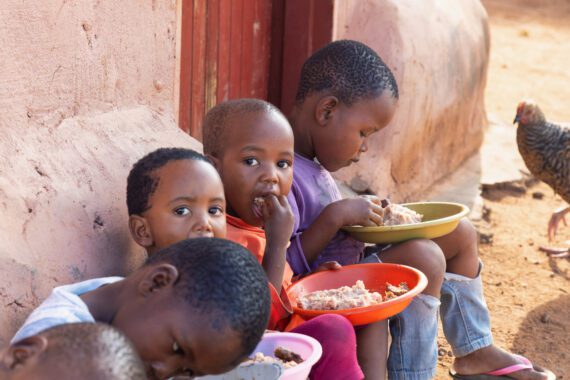

Bread members focus on the most vulnerable children. One of the most vulnerable groups is the youngest children, the age group that has been known as the “1,000 Days” since 2008, when researchers established definitively that the 1,000 days from pregnancy to the second birthday is the most important window for human nutrition.

This is because it is a window of both great opportunity and great risk. Pregnant women, babies, and toddlers need the right nutrients at the right times. Eating foods that contain these can establish a lasting foundation for a healthy life. But even with progress over the past 20 years, far too many children do not get what they need. They are at far greater risk of dying from childhood illnesses or infections. Those who survive may suffer from stunting, a condition that brings lifelong health problems and damage to physical and cognitive development. About one child in five alive today suffers from stunting.

Strenuous efforts to reduce the rates of stunting must continue if the world is to meet the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), goals that Bread often mentions, by 2030.

The world has made impressive progress over the past one to two generations in ensuring that children reach their milestone fifth birthday. When we mention childhood malnutrition, we are generally talking about children younger than 5. This is because, while older children, teens, and adults can also suffer serious consequences from malnutrition, they are better able to recover than young children.

Among children born around the world in 1990, one child in 11 did not survive to age 5. Among children born in 2022, this figure drops to one child in 27. While this is still far too many, it also shows significant progress. The U.N. Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the predecessor of the Sustainable Development Goals, called for reducing the neonatal mortality rate by two-thirds by 2015, compared to the rate in 1990. The MDGs spurred national efforts to advance more rapidly in areas such as public health, immunization against childhood diseases, clean water, skilled attendants at birth, and micronutrient supplementation, all of which contributed significantly to the progress. Expanded educational opportunities and achievement for girls was another key contributing factor. About 60 countries met the goal by 2015.

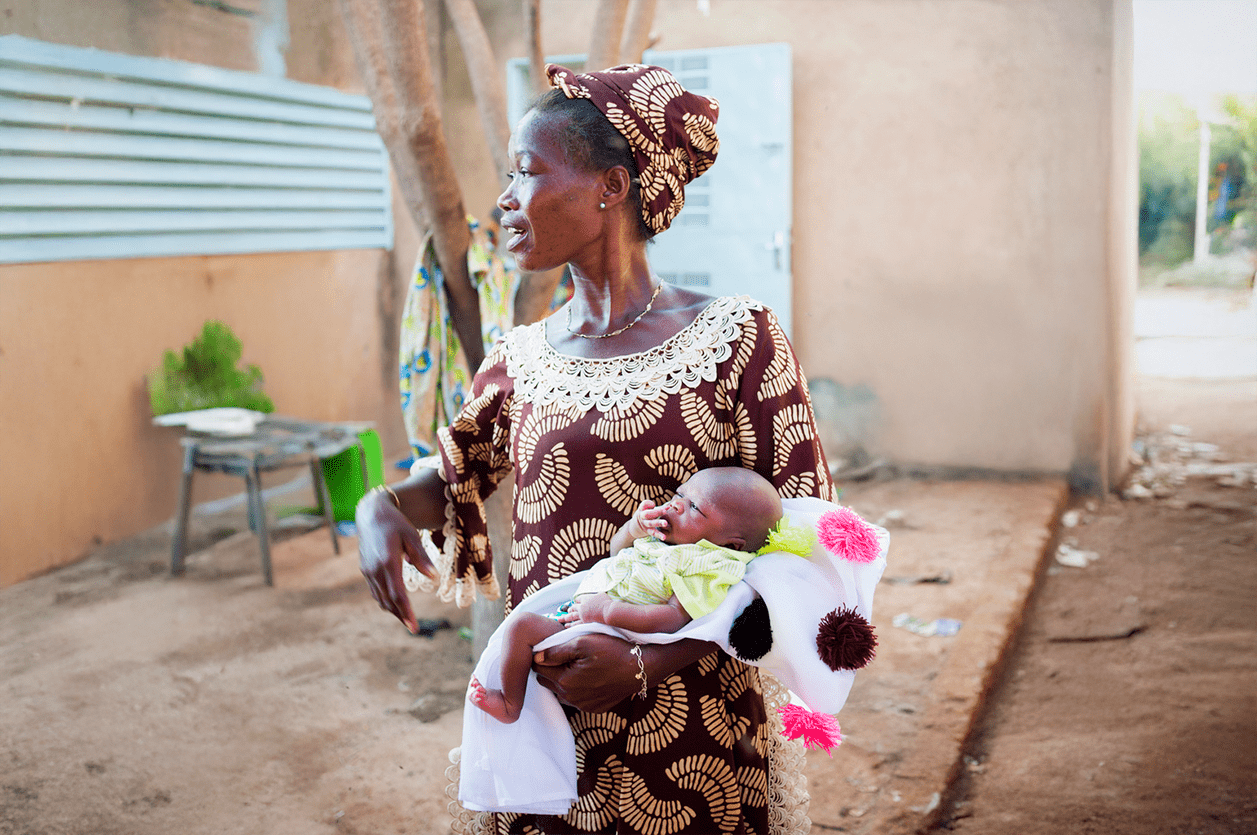

Many more children who are between one month and 5 years old are surviving. As their survival rate increases, a larger and larger share of those who die are newborns. The most fragile time in human life is birth to four weeks old, sometimes called the “neonatal period.” Progress on reducing mortality among these babies has also been made, but at a slower pace. This means that a larger share of all deaths of children under 5 are of babies in the first month after birth. The need to save newborn lives is receiving more attention now that childhood deaths are more likely to be those of newborns.

- As of 2019 (latest available data), 47 percent of all deaths among children under 5 occur during the first four weeks, about one-third on the day of birth. Nearly three-fourths occur within the first week.

- Also in 2019, Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest neonatal mortality rate, 27 deaths per 1,000 live births. The second-highest rate was in Central and Southern Asia, with 24 deaths per 1,000 live births.

- According to the World Health Organization, a child born in a sub-Saharan Africa or Southern Asian country is 10 times more likely to die in the first month than a child born in a high-income country.

When we look at neonatal survival worldwide, we realize that in lower-income and higher-income countries alike, some babies do not survive. They are born far too early and/or with severe congenital conditions, and today’s medical knowledge cannot save their lives.

Most other causes of neonatal mortality, however, show stark inequities, particularly among premature newborns. Many newborns die simply because of where they were born.

Researchers and medical professionals have developed a clear understanding of some relatively straightforward ways of improving the survival of newborns and reducing preventable stillbirths. An effective strategy must include sufficient high-quality prenatal care, skilled care during birth, postnatal care for mother and baby, and identification and medical attention for babies who have low birthweights or illnesses. Often what is needed, however, is not expensive technology, but a system of trained midwives who provide continuity of care. In fact, continuity of care can reduce preterm births by up to 24 percent.

In lower-income countries, babies continue to be born without the support of a trained healthcare provider, although this is becoming less common. Those born in rural areas, far from the nearest well-equipped clinic or hospital, are at higher risk, as are those born to women who have not had four or more prenatal checkups.

But the main risk factor for newborn death is premature birth. Complications from prematurity is the leading cause of death among children under 5 worldwide. In 2019, there were approximately 900,000 deaths among premature infants.

In our next piece, we will look at some solutions that are enabling more babies to survive and how some countries are meeting with success in implementing them.

Michele Learner is managing editor, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.