By Jack Wallis

The United States has been a leader in global humanitarian assistance for more than 50 years. Since its beginnings in 1954, Food for Peace has provided nutrition assistance to more than four billion people worldwide, and policymakers in both parties have worked together to support people who are confronting hunger.

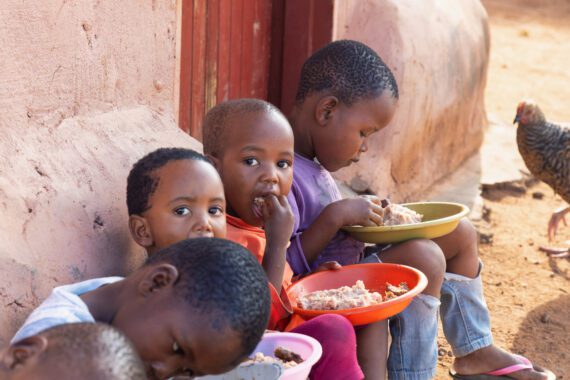

Over the past several decades, the world made significant progress against hunger. However, since the late 2010s, armed conflict, climate change, and economic shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic have raised hunger rates and threaten to reverse more hard-won progress. It is essential for the global community, national governments, and communities to keep working to save children’s lives, meet people’s basic needs for food and health care, and enable them to recover and rebuild.

The 2024 Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC) reported that in 2023, more than 700,000 people, the highest number on record, lived in famine conditions. The most recent update from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) identified 18 hunger hotspots and highlighted the most urgent humanitarian actions in each country or region. It described conditions in the hotspots of highest concern: “In Palestine, South Sudan, Mali, Sudan, and Haiti, humanitarian action is critical to prevent starvation and death.”

Donor countries can, by providing sufficient funding for emergency food aid, save the lives of countless babies and toddlers. This is an achievable goal.

U.S. humanitarian assistance is provided through several programs that are administered by federal agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Each method of providing people with food has advantages and disadvantages. An effective approach would be to tailor aid methods to best serve each community.

Some assistance is given in the form of U.S. commodities that are shipped to the sites of hunger emergencies. This is a good choice in cases where there is not enough food in the immediate area—for example, if there is widespread harvest failure.

But often, shipping commodities can be harmful to local markets. It is important to consider the potential impact on local farmers of introducing large quantities of free food. This could effectively put market sellers out of business; they may not be able to buy seeds and other essential supplies for the next planting season.

In other cases, U.S. funding is used for local and regional purchase (LRP), meaning that food is purchased from markets in nearby areas and distributed where it is needed. Local and regional purchase is an effective strategy when markets nearby have sufficient food to meet the need. As with U.S. commodities that are shipped to the area, however, it is important to avoid distorting local markets.

In still other cases, families are given cash or cash vouchers, often electronically transferred, so they can buy food locally. Cash transfers work well when local markets have sufficient food, but people can’t afford to buy it; when people are scattered over a wide area; or when individuals or groups are moving in search of a safer area.

Cash and vouchers have the advantages of enabling people to buy familiar foods that best suit their needs and support local markets. It is faster and less expensive to make them available. They also help people in difficult and often unfamiliar situations regain a sense of agency in their own lives.

Despite our country’s long history of providing support to people vulnerable to hunger, U.S. agricultural and shipping interests have advocated for policies that would limit the effectiveness of that mission.

Regulations now in place make food delivery more expensive by requiring that much of the funding be used to purchase U.S. commodities. There is also a requirement that 50 percent of all aid shipments be sent on a U.S. flagship. Because there are relatively few of these ships, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that shipping costs were 23 percent higher on average than they would otherwise have been. Shipping from the United States can also take months.

Understanding the nuances of particular humanitarian emergencies allows us to promote support tailored to local markets and people. It is important to enable agencies such as USAID and USDA to provide aid that promotes sustainability and self-sufficiency in hunger crises. Bread for the World supports food aid policies that allow flexibility so that lifesaving food aid can reach malnourished children and others in need as quickly as possible. Prioritizing policies that make the best use of U.S. funding can save lives, empower people in vulnerable communities, and help local economies recover.

Jack Wallis is an international hunger intern, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.