An estimated 45 million children under 5—that’s almost 7 percent of all children in this age group—are suffering from the most dangerous form of malnutrition, known as childhood wasting. In the United States, the word is most commonly used in the phrase “wasting away.”

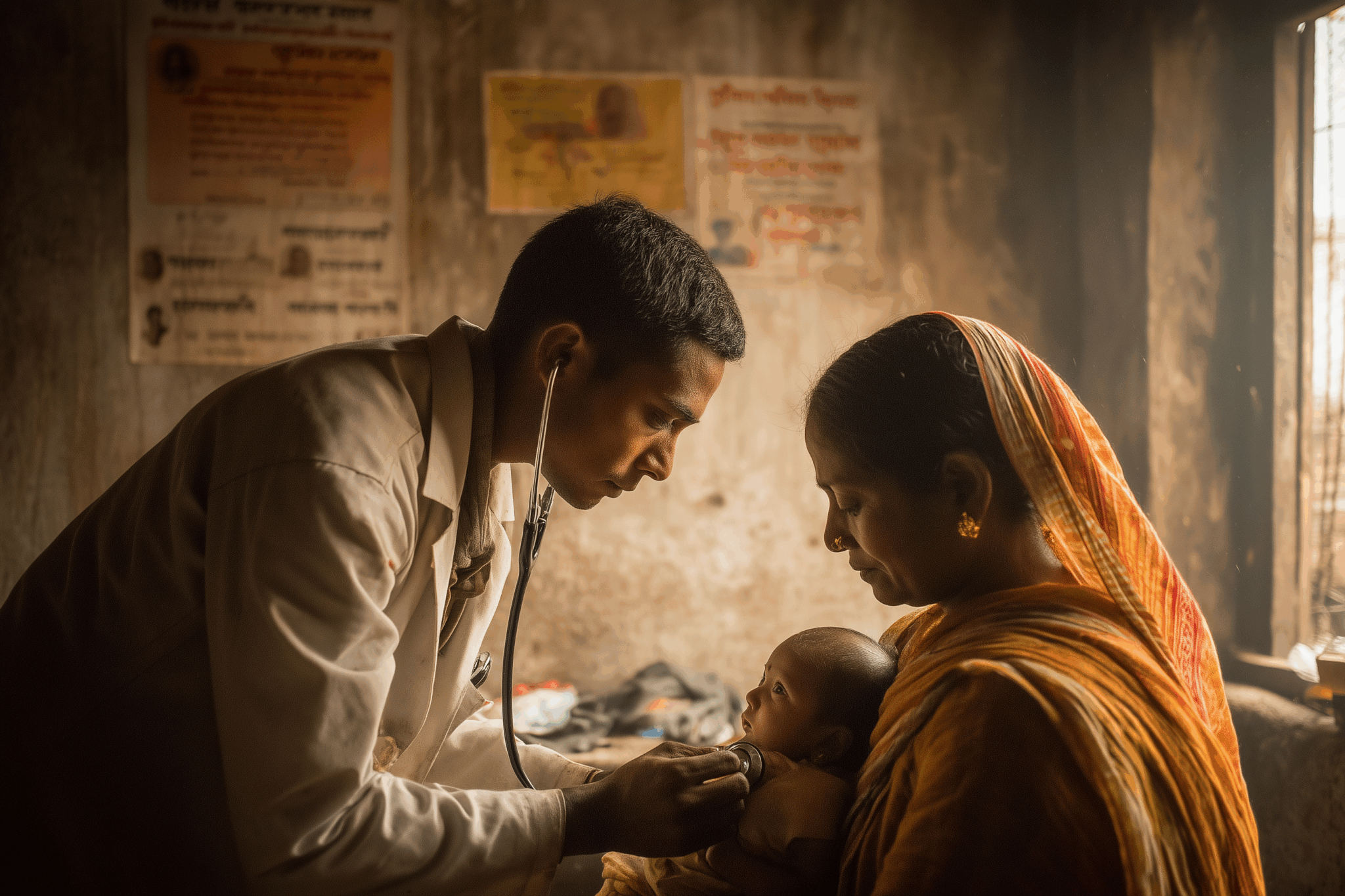

Also known as Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM), wasting is significant and sudden weight loss caused by illness and/or eating less food. Children weigh far too little for their height. Children with acute malnutrition have weakened immune systems, making them more vulnerable to childhood diseases and other illnesses that are unlikely to pose a risk to well-nourished children.

In fact, children with severe wasting are 12 times as likely to die as a healthy child. The famine in Somalia in 2011, for example, led to the deaths of an estimated 130,000 children under 5. The top causes of death were diarrhea and measles.

The Global Action Plan on Child Wasting was first released in 2019, but in January 2023, with child malnutrition still on the rise, five UN agencies called on the global community to step up the implementation of the plan.

The plan focuses on the 15 countries most affected by child wasting, aiming to prevent and treat acute malnutrition, which affects more than 30 million children in these countries. They are Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen.

Experience has shown that it is essential to use a “multisectoral” approach, which means simply working with agencies from different parts of the government—for example, health, food, water and sanitation, and social protection. This is because the issues are interconnected.

As Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus of the World Health Organization explained, “The global food crisis is also a health crisis, and a vicious cycle: malnutrition leads to disease, and disease leads to malnutrition.”

This is evident in Haiti, one of the 15 countries targeted for efforts to reduce wasting, where cholera killed an estimated 10,000 people in 2010. A resurgence of the disease began in October 2022.

In its most recent version, covering November 2023 through April 2024, the Hunger Hotspots update produced by humanitarian agencies describes Haiti as of very high concern. Conditions are deteriorating, and an estimated 1.4 million people are projected to be living on the verge of famine during the months March through June 2024. In some parts of the country, 30 percent of the population is severely malnourished.

The hunger crisis in Haiti is driven by violence, disasters due to the country’s vulnerable location as well as accelerating climate change, and weak government capacity. Violence has soared since the assassination of President Jovenel Moise in July 2021. Noncombatants are frequently the target of attacks or caught in the crossfire between warring factions.

Haiti’s food production efforts have been significantly damaged by the fighting itself and by uncertainty about where fighters are located and what they might be planning to do next. In many cases it is too dangerous for farmers to work in their fields. Crops and stored food are sometimes seized or destroyed. Women and girls, even traveling in groups, are terrorized by mass rape.

The fall 2023 upsurge in violence in Artibonite, Haiti’s main rice-growing region, has worsened hunger still further. UNICEF said that at least 115,000 children in Haiti are believed to be suffering from life-threatening malnutrition in 2023—an increase of 30 percent over 2022. In Artibonite, the number of children who are estimated to need lifesaving treatment has more than doubled since 2020.

Humanitarian workers reported that insecurity has made it extremely difficult, and in some cases impossible, to access six of the department’s 17 communes. They include Saint Marc, Verrettes, and Petite Rivière.

Cholera is a water-borne disease, so it is especially concerning that two of the three major water treatment plants in Artibonite have shut down due to insecurity, and the third faces distribution challenges.

“No human being, and certainly no child, should ever have to face such shocking brutality, deprivation, and lawlessness. The current situation is simply untenable,” said UNICEF Executive Director Catherine Russell.

Bread for the World has long advocated for U.S. policies that both save lives in the short term and end hunger in the medium term—in hunger hotspots, and in all other countries where children suffer from malnutrition and wasting. The “whole of government” approach to reducing acute malnutrition—with the engagement of the ministries of health, social protection, food, and water and sanitation—has the potential to make lasting progress against wasting.

Bread also supports the efforts of UN agencies to speed up implementation in 15 countries of the Global Plan—the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Michele Learner is managing editor, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.