Bread for the World has been a strong advocate of strengthening the federal Child Tax Credit (CTC). As of publication in November 2024, Bread continues to work to persuade Congress to enact a permanent expansion of the CTC, one that would allow all low-income families with children to qualify for the credit.

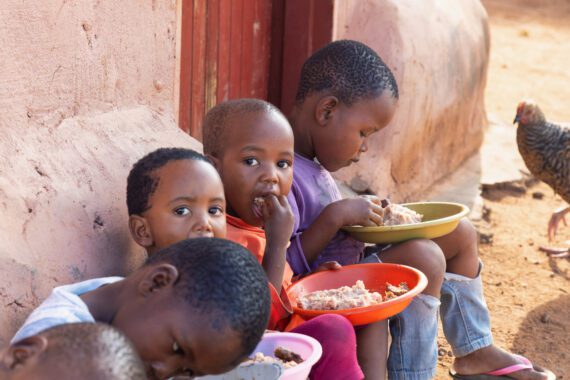

The idea is straightforward: an expanded CTC would put more money in the pockets of working parents who are struggling to put food on the table.

We have solid evidence that a permanent expansion of the CTC could significantly reduce the rate of childhood hunger in the United States. This evidence can be summed up as the results of a similar but temporary CTC expansion just three years ago. The American Rescue Plan of 2021 increased the amount of the CTC and made payments monthly rather than structuring the benefit as a lump sum paid as a federal tax refund. For six months, from July 2021 through December 2021, millions of additional families with children received monthly benefits of $250 for each of their children ages 6 to 17 and $300 for each child under 6.

For our country’s lowest-income families, an even more important provision of the CTC expansion was that all families with children, including households whose taxable incomes had previously been too low to be eligible, could now qualify for the full CTC amounts. As recently as 2018 (latest data available), an estimated 27 million children lived in these households.

The impact was immediate: a steep decline in parents reporting that their families did not have enough food. On August 16, 2021, 25 percent fewer parents reported food insecurity than on July 5, 2021.

In addition to its essential role of enabling more families to meet their immediate needs, an expanded CTC has a second important long-term benefit: contributing to racial, gender, and class equity in our country. As Bread has discussed, equity requires making conditions fair for all. Policies that promote equity help to move everyone closer to a “starting point,” whether they started out or continued being “left behind” because of disability, poverty, racial or gender discrimination, or a combination of these and other factors.

Most people realize that raising children is expensive. As a group, families with children are more likely to be food insecure than families without children. But the risks are even higher for some demographic groups and family structures, including Black families, Latino/a families, Native American families, and families with single mothers, among others. (Other families with higher rates of food insecurity include, for example, families with single fathers and families with parents living with a disability).

When all families with children are eligible for the same CTC amounts, there is a greater benefit for families at higher risk of hunger, because these dollars make up a larger part of their total income. This is even more likely to be the case for families who belong to more than one marginalized group—perhaps a family whose single mother is Black or Native American or biracial.

Researchers projected that children from groups with disproportionately high poverty rates would benefit most from the 2021 expansion. Poverty rates would be cut by 62 percent, 52 percent, and 45 percent among Native American children, Latino children, and Black children, respectively. The children of single mothers have very high poverty rates. At the height of the pandemic in 2021, for example, the national poverty rate for households with single mothers was 31.3 percent. Mothers of color and their children had even higher poverty rates: 37.4 percent of Black families, 35.9 percent of Hispanic/Latina families, and 42.6 percent of Native American families with single mothers.

We sometimes think or talk about the CTC as a program for low-income people, but this is not the case. Almost all families with children except the very poorest are eligible. The gap between the lowest-income families with children and other families with children will widen if all families except the poorest receive the CTC benefit.

The CTC’s restrictions on high-income families–$200,000 for individuals and $400,000 for married couples—exclude just a small percentage of families. A single parent with an income of $200,000 is at the 95th percentile of individual income earners, so only the 5 percent whose incomes are higher than hers would be ineligible for the benefit.

Bread is deeply disappointed that a bipartisan version of the CTC expansion stalled in the U.S. Senate. Passage of this expansion would make more grocery money available to millions of parents whose jobs do not pay enough to make ends meet. Even when Congress does not act, children still need to eat.

Yet, that proposed expansion would include not all low-income families with children, but, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, only those with incomes of about $16,000 or more per year. Such a policy excludes millions of families who work full-time but are paid less. For example, a family might be composed of a woman who lives with her two children in Georgia, Wyoming, or Tennessee. She works 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, at the federal minimum wage. Her annual income is $15,080 before taxes.

Georgia, Wyoming, and Tennessee are three of the seven states whose minimum wage is the same as the federal minimum wage. The federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour. It has been $7.25 an hour, with no adjustments for inflation, for 15 years now – since 2009. A CTC that does not exclude the lowest-wage workers would make a big difference in the lives of children whose parents belong to a group often referred to as “the working poor.”

Michele Learner is managing editor, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.