Building Political Will to Reduce Child Malnutrition in Peru

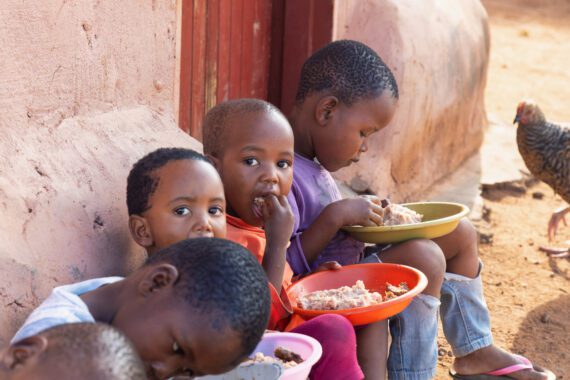

Peru has shown that it is possible to make extraordinary progress against childhood malnutrition. Since 2006, the stunting rate of children younger than 5 has been cut by more than half. According to the latest national survey, it is now at 12 percent.

Peru’s success can be credited broadly to political will, but other countries could learn from more specific information about how Peru was able to make malnutrition a top priority for national policy.

In 2006, an alliance of national NGOs, led by CARE Peru and including USAID and other international partners, challenged presidential candidates to commit to a specific goal: to reduce stunting among children younger than 5 by 5 percent in 5 years, “5x5x5.” Candidates embraced the goal, although the catchy slogan wasn’t the reason. Rather, they were persuaded by the alliance’s presentation of the results of its own efforts to reduce stunting in various parts of the country. It used a carefully coordinated multisectoral approach, meaning one that brings together personnel and knowledge from several different fields. In this case, the main sectors were agriculture, water, sanitation, and health. The alliance offered to help the government achieve 5x5x5.

Presidential candidates knew about feeding programs, which had operated in Peru for many years but had made no progress on stunting. In some rural areas, more than 60 percent of young children were stunted. Leaders needed to learn about the multiple causes of malnutrition and its role in depressing economic growth and perpetuating cycles of poverty.

Once the candidates committed to achieving the 5x5x5 goal, the alliance announced this publicly, which got the attention of national media, including the largest newspapers and radio stations. “Getting candidates to commit to a target for anything had never been done before, and that made a huge difference—it gave the campaign a focus,” said Milo Stanojevich, director of CARE Peru during this breakthrough decade.

Alan Garcia, the candidate who was elected president, ratified his commitment to 5x5x5 and included it in the organization of his new government, directing ministries to work together to achieve the goal. Garcia even upped the ante by pledging to reduce stunting by 9 percent during his 5-year term of office.

The government could be seen following through on its commitments, which engendered other good faith efforts by key partners, such as the World Bank and the country’s business community. The World Bank, which was working with the Peru Ministry of Finance to introduce a model of “budgeting by results,” used the alliance’s causal framework for child malnutrition as a prototype for the new system. A large share of Peru’s economy is based on natural resource extraction. Under an agreement with the government, mining companies agreed to dedicate a share of their royalties to achieving the goal.

The previous government had established a national conditional cash transfer program. These programs gave parents, usually mothers, cash grants in exchange for taking actions such as having a child vaccinated or sending all her children to school. The Garcia administration expanded this program with a focus on actions that help reduce stunting.

“It seemed like everyone was talking about malnutrition,” Stanojevich said.

Such a strong commitment to addressing a problem demands proper monitoring and evaluation. Everyone wants an answer to “Are we on track?” The capacity to collect periodic data was not strong in many rural areas. With help from USAID, Peru’s national statistics institute began to administer health surveys annually rather than every three years. It also used larger sample sizes so that the data could provide more detailed information about conditions at local and regional levels.

President Garcia’s term ended in 2011, but the alliance played a key role in ensuring that nutrition remained a national priority and that successful strategies were maintained by subsequent governments. “We are proud of our advocacy, but advocacy does not take programs to scale,” Stanojevich said. “We just kept the pressure on and kept the support through three different administrations, and the government made it happen.”

Print or Download Report Materials

2019 Hunger Report Executive Summary

Ending hunger is within reach. 2030 sounds audacious. But decades of victory over hunger, despite recent setbacks, reveal a different picture. It is rapid global progress, not any one which persuades us that ending hunger and malnutrition is possible sooner rather than later.

Christian Study Guide

The study guide offers a biblically-based tool to explore God’s call to protect vulnerable people in the 21st century. The guide summarizes the report’s overall themes and provides discussion questions and group activities on select topics in the report.

Introduction: Ending Hunger is Within Reach

A national effort to end hunger could bring our country together and this goal has in fact, already brought the world together. Ending hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030 is one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in 2015 by the governments of 193 countries, including the United States, with support from their civil society and business sectors.

Chapter 1: Livelihoods

The only way to end hunger with dignity is to enable people to earn the income they need to provide enough healthy food for themselves and their children.

Chapter 2: Nutrition

Maternal and child nutrition is a critical factor in healthy human development. Nutrition is a lifelong necessity for the health and well-being of individuals, their communities, and ultimately their countries.

Chapter 3: Gender

Women in every society are treated as less valuable and/or less capable. Women and girls are the largest group of marginalized people. Yet food security is dependent on them.

Chapter 4: Climate Change

Populations that are most affected by the impact of climate change are those most likely to be hungry. Climate change is the biggest barrier to ending hunger once and for all.

Chapter 5: Fragility

When marginalized groups or people living in extreme poverty turn to violence, hunger is very often an underlying factor. Hunger is both a cause and an effect of the violence associated with fragile environments.

Religious Leaders’ Statement

“As followers of Christ, we believe it is possible to build the moral and political will to end hunger by 2030. The world has made unprecedented progress against hunger, poverty, and disease in recent decades. The United States has made progress more slowly than many other countries, but it is feasible to end hunger here, too.” — excerpt from religious leaders’ statement

Hunger Report Sponsors

Co-Publisher: Margaret Wallhagen and Bill Strawbridge; Partners: American Baptist Churches USA World Relief, American Baptist Home Mission Societies, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, Christian Women Connection, Church of the Brethren, Community of Christ, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, Covenant World Relief/Evangelical Covenant Church, Evangelical Covenant Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Growing Hope Globally, Independent Presbyterian Church Foundation, International Orthodox Christian Charities, National Baptist Convention, USA, INC, Society of African Missions, United Church of Christ, Women’s Missionary Society of the African Methodist Episcopal Church