This story is featured in the 2020 Hunger Report: Better Nutrition, Better Tomorrow

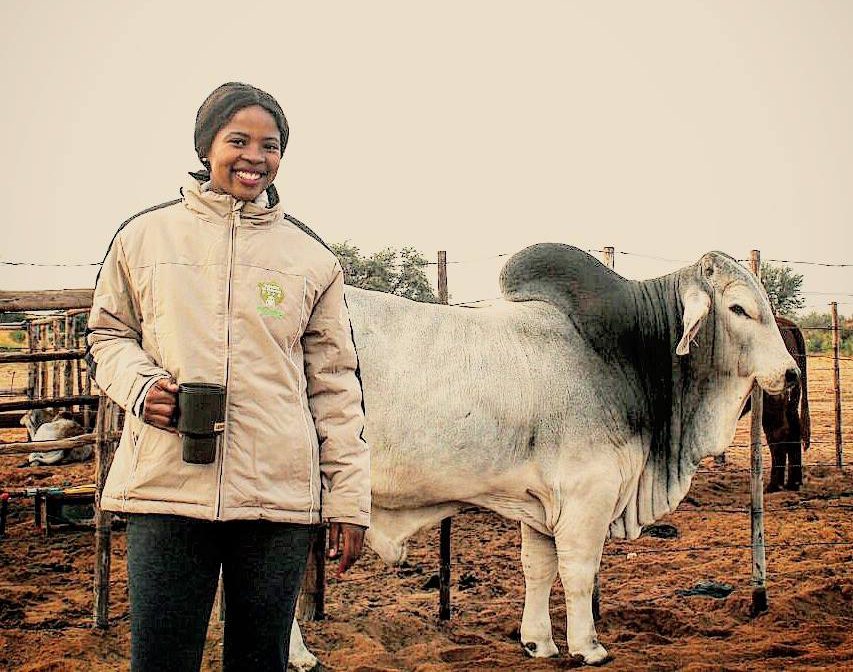

Pearl Gaone Ranna is a mother, a farmer, a social entrepreneur, and a visionary. At 25, she is already a leader of youth and women in the agricultural sector in her country of Botswana and beyond.

In 2016, just two years out of college with a bachelor’s degree in business, she convened the first-ever women in farming expo held in Botswana, drawing participants from across Southern Africa to network and discuss the barriers and opportunities they face in their respective countries. She is the founder and managing director of Unitech Farming, which provides training and support to youth and female farmers, most of whom are smallholders operating on a couple of acres or less.

Women farmers in Botswana have advantages many of their peers in neighboring African countries do not. For example, female farmers in Botswana can own land, the most precious asset to farmers everywhere. But laws promoting gender equality don’t lead immediately to changing stereotypes, and women farmers in Botswana continue to struggle to gain recognition for their contributions to food security. Many internalize negative stereotypes that women can’t farm as well as men, and that’s what Ranna is determined to change.

Unitech has trained hundreds of women in basic capacity-building to run a successful farming enterprise. The national government has just rolled out a school feeding program for all children in primary grades and plans to source much of the foods from local farmers. It’s a tremendous opportunity for all farmers to join, especially those who can break out of subsistence production, such as those women being targeted in its new program for mothers with young children.

“You can’t believe how hard it is to run your own business as well as raising a child,” says Ranna, who has firsthand knowledge, having experienced those challenges running a poultry operation while raising a daughter.

The program includes an early childhood development center for the children, so that while their mothers are receiving training and working on their farms the children are well cared for in a center-based learning environment. Revenues the women generate with increased productivity on their farms will go towards sustaining the program to provide training to new groups of women.

If the program is successful, as she believes it will be, she hopes it will contribute to policy changes that institutionalize such support for women farmers nationwide. “I am trying to advocate for policies for women and youth,” she explained. “To advocate effectively you need to be able to show something works.”

Ranna is excited, in part, because the program is being launched in the village where she was raised. She fell in love with farming as a teenager helping on her mother’s farm. She says her father wanted her to set her sights higher than being a farmer. Indeed, she did. She intends to transform the agricultural sector for all women.

The persistence of global hunger has more to do with poverty and weak governance than production shortfalls