Conflict is one of the main causes of hunger around the world. Hunger increases when conflict forces people to abandon their land, homes, and jobs and when food assistance can’t reach an area because of violence. Conflict also destroys valuable agriculture and infrastructure.

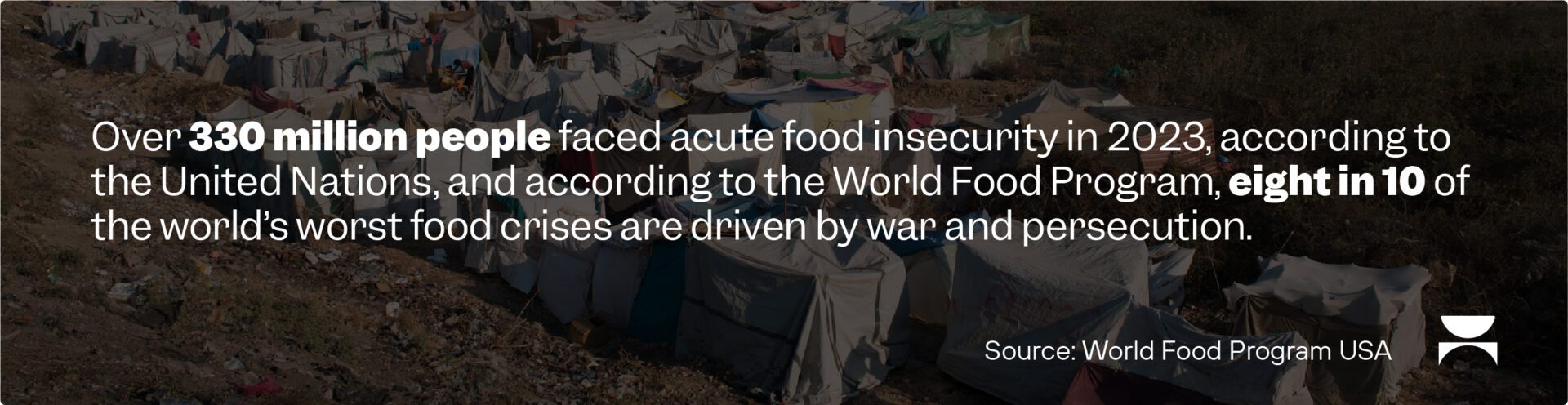

Over 330 million people faced acute food insecurity in 2023, according to the United Nations, and according to World Food Program USA, eight in 10 of the world’s worst food crises are driven by war and persecution.

Places like Sudan, Haiti, and Gaza are in dire need of urgent humanitarian assistance to address acute food insecurity from war, violence, and political turmoil. But they’re not the only ones experiencing such strife; according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which ranks violent conflict levels around the world, 50 countries rank as having extreme, high, or turbulent levels of conflict.

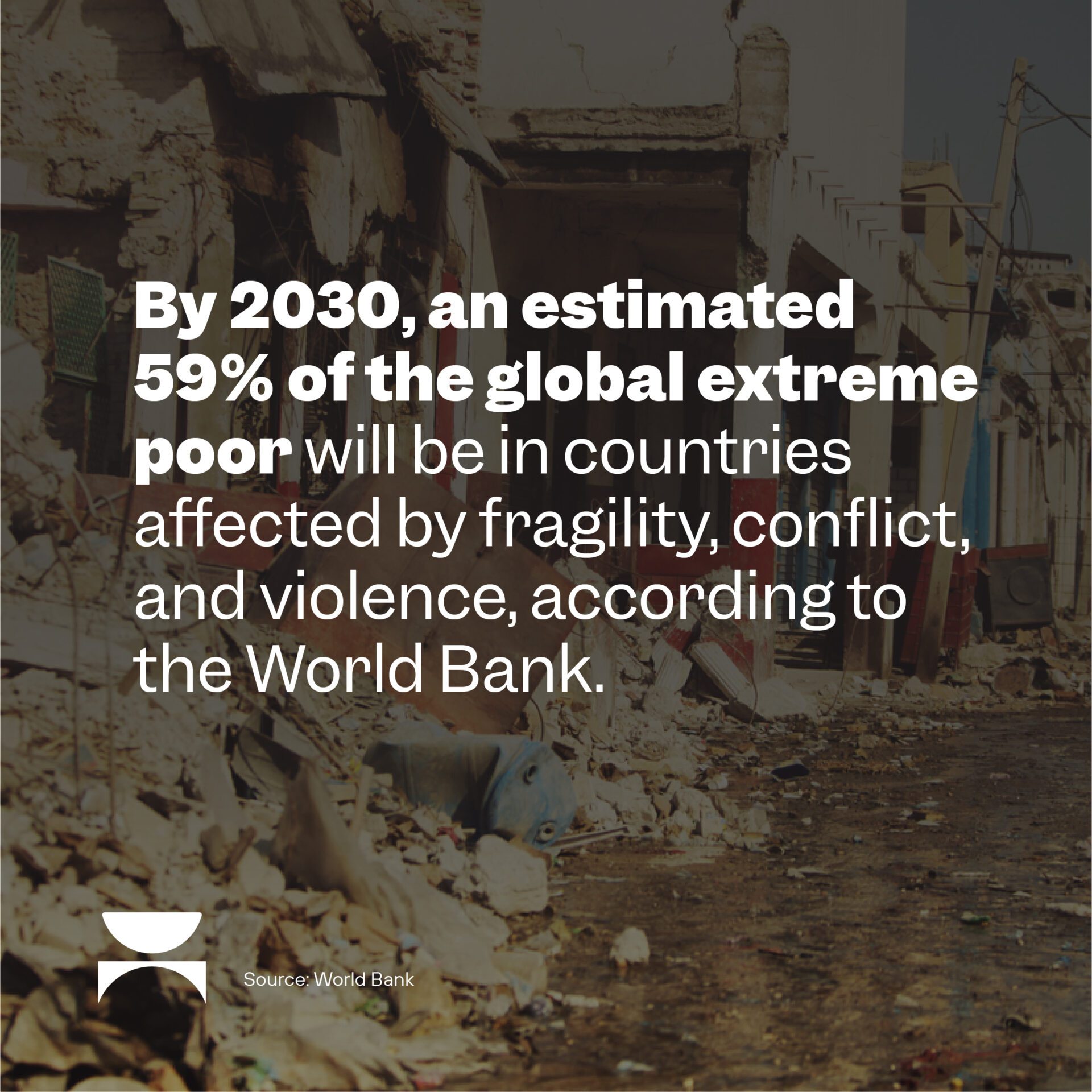

By 2030, an estimated 59% of the people experiencing extreme poverty globally will be in countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence, according to the World Bank.

At Bread, our mission to end hunger is driven by faith, integrity, and a commitment to justice. We urge U.S. decision makers to do all they can to achieve equitable systems and policies, not just in the United States but around the world. Ending conflict-driven hunger is a complex task that requires commitment at the highest levels of government, in collaboration with international financial institutions, nonprofits, and communities of faith around the world.

How does conflict impact hunger?

Violent conflicts occur when organized groups or institutions, sometimes including the state, use violence to settle grievances or assert power.

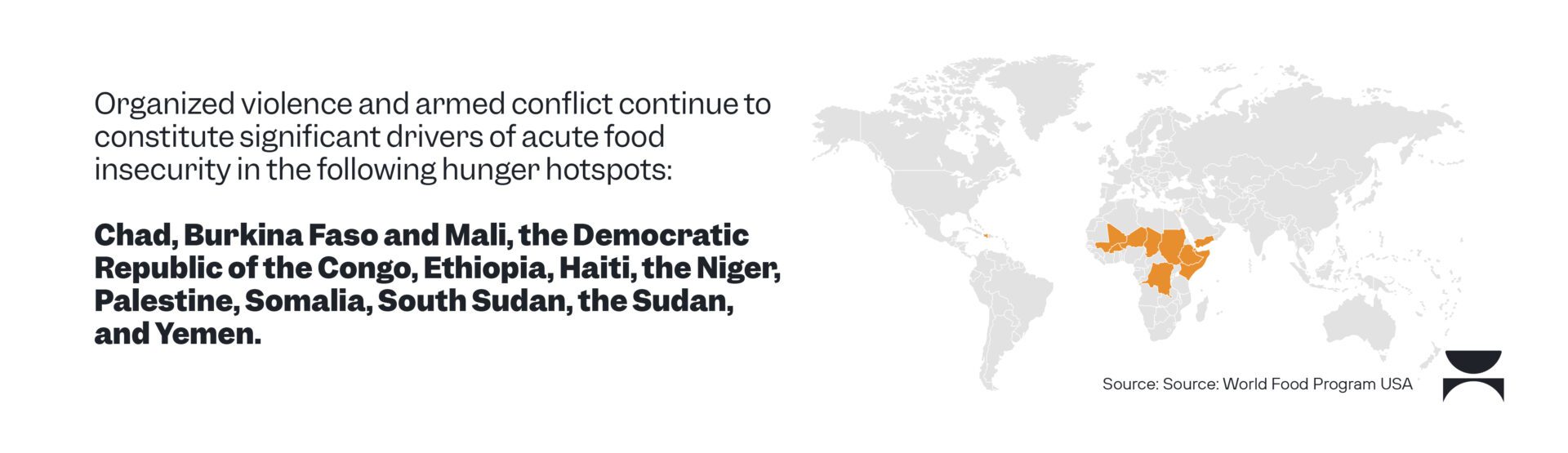

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization’s and World Food Program’s November 2023 to April 2024 outlook (citing ACLED), global levels of violent incidents remained at high levels between June and September 2023. Organized violence, armed conflict, and insecurity continue to constitute significant drivers of acute food insecurity in the following hunger hotspots: Chad, Burkina Faso and Mali, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, Niger, Palestine, Somalia, South Sudan, the Sudan, and Yemen – and the list continues to grow.

Conflict causes hunger in several ways. For the majority of people in low-income countries, agriculture is the primary way that they feed themselves and maintain a source of income; conflict can destroy land and valuable agriculture. It can disrupt roads, railways, and air transport, meaning it becomes difficult to move food from place to place. It also displaces people from their homes and jobs, leaving them without a way to feed their families.

Conflict is also particularly dangerous to food security because war and violence can prevent outside humanitarian assistance from reaching the most vulnerable populations. And it is increasingly common for armed groups to use hunger as a weapon of war, deliberately cutting communities off from food sources. People become trapped, and hunger, malnutrition, and illness soar.

Who is most affected by conflict?

Women and children are most affected by conflict-driven hunger. And nearly 60 percent of those facing severe hunger are women and girls. Oftentimes, when there is limited food available, women eat last and least.

Additionally, women and children are more likely to be displaced, making up 80 percent of the refugees worldwide. Many of these children will never return to their homes and can be separated from their families while traveling, putting them at an increased risk of violence, abuse, trafficking, and military recruitment.

Conflict and Hunger: Gaza

Women and children are especially vulnerable in Gaza. According to The Washington Post, as of April 2024, more than 90 percent of young children and pregnant and breastfeeding women in Gaza are subsisting on two or fewer food groups per day.

The Gaza Strip borders the Mediterranean Sea, between Egypt and Israel, and is a little more than twice the size of Washington, D.C. It has a population of 2.2 million people. Conflict in Gaza escalated in October 2023 when Hamas launched a deadly attack on Israeli citizens, and Israel responded with an ongoing invasion of the Gaza Strip with the stated goal of destroying Hamas.

In 2024, Gaza has become “a fight of bread versus bombs,” as InterAction president and former Bread board member Tom Hart put it in an April 2024 op-ed. According to the United Nations, of the 700,000 hungriest people in the world, four in five live in Gaza. One in three children under the age of 2 in northern Gaza is suffering from severe malnutrition – the highest level of child malnutrition anywhere in the world.

Famine is now happening in parts of Gaza, as United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Administrator Samantha Power has acknowledged.

Very few aid workers and food convoys have been able to reach residents amid the violence. Gen. Michael “Erik” Kurilla, commander of U.S. Central Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March that during a recent visit, he saw 2,500 aid trucks held up outside the gates, awaiting clearance to bring supplies into Gaza.

The United States has taken steps to provide food assistance, such as air drops of aid in early March, and has built a floating maritime pier off the coast. But, to provide true relief, there is a need for an immediate and lasting ceasefire and sustained access to humanitarian aid, including restoration of food delivery, cross-border water pipelines, and resumption of electricity distribution.

Conflict and Hunger: Sudan

The United Nations warned in March 2024 that the war in Sudan is “triggering the world’s largest hunger crisis.” More than 20 million people are facing acute food insecurity in Sudan, a number that’s nearly doubled since last year. More than 10 million have been displaced from their homes (inside and outside the country) since mid-April 2023. Nine in 10 people across the country, which is located in Northeast Africa, face “emergency levels of hunger.”

In April 2023, fighting broke out between the forces of two rival generals – army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who leads Sudan’s Armed Forces (SAF), and the head of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. Since then, there have been reports of mass killings, indiscriminate targeting of civilians, and sexual violence, and humanitarian access has been limited.

Those regions most severely impacted include Khartoum, South and West Kordofan, as well as Central, East, South, and West Darfur. Without a resolution or assistance, families and refugees are at risk of starving to death.

Conflict and Hunger: Haiti

With a population of 11 million people, Haiti is located between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean – about 700 miles from Miami, Florida. Violence by armed gangs throughout the country has skyrocketed since President Jovenel Moise was assassinated in July 2021. Then, in early March 2024, gangs attacked two of Haiti’s largest prisons, resulting in the escape of almost 4,000 prisoners. On March 12, 2024, Haiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry announced his plan to resign.

As of April 2024, nearly five million people are facing extreme hunger – including more than 1.6 million people on the brink of starvation. Over 300,000 Haitians have fled their homes, and in the Artibonite department, armed groups have blocked farmers from delivering their produce to the market.

The international community is struggling to reach people affected by the conflict, especially as armed gangs attempted to seize control of Port-au-Prince’s Toussaint Louverture International Airport in March. In addition, numerous schools have remained closed, which has resulted in more than 300,000 students being unable to access school feeding programs.

Restoration of a democratic government is critical for peace and stability for the Haitian people.

What does global hunger have to do with national security?

Access to food and national security are tightly connected. Security is only possible when communities have the resources they need to survive.

Alleviating hunger by addressing conflict and stabilizing individual and community livelihoods means that people are less likely to need to leave their homes, resort to criminal activity, or fall prey to radicalized groups.

What can the U.S. government do to break the cycle of conflict and hunger?

The United States is in an important position of influence and possesses resources that can help resolve conflict and hunger around the world.

In April 2024, the Senate passed a $95 billion national security supplemental package. This package allocated more than $9 billion for humanitarian aid, aimed at delivering crucial necessities such as food, water, shelter, medical care, and other essential services to civilians in Gaza, the West Bank, Ukraine, and other conflict-affected regions worldwide. This package will help improve the lives of those who are most vulnerable around the world.

The Global Fragility Act (GFA) was passed in 2019 to reform the way the U.S. government conducts conflict prevention and stabilization operations. The GFA was designed as a 10-year effort. Bread urges U.S. leaders to implement the Global Fragility Act and increase the number of countries covered by this Act, such as Sudan, Yemen, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

We urge our nation’s leaders to follow these principles to prevent and respond to the conflicts and fragility that are contributing to so much of the hunger around the world:

1. Invest in the capacity of communities to solve problems.

Because prevention is less costly – in human life and suffering, in money, in time – than responding to events that have already happened, it is more effective to focus on building resilience and addressing the root causes of shocks, including hunger, poverty, and violence. Foreign assistance should work in concert with diplomatic strategies to foster equitable policies, peace building, and adaptation to climate change.

2. Partner with other governments, multilateral institutions, and civil society in fragile countries to meet the basic needs of people and build strong institutions.

No single actor can manage the complexity of strengthening fragile countries. Inclusive, coordinated approaches building on the experience and interest of all stakeholders are more likely to succeed. Community-driven approaches, such as support for local faith institutions, schools, or clinics, have worked well in many fragile or conflict zones. U.S. efforts should focus on strengthening local institutional capacity.

3. Build human and institutional capacity to reduce human suffering.

Scarce resources should be applied in the areas where they matter most to address the needs of the most vulnerable populations – most often women, children, and indigenous communities that have been systematically oppressed. In addition, strengthening local civil society and governance institutions can build capacity to support communities and minimize scarcity and suffering. This can include investing in agricultural infrastructure to boost food security, nutrition, livelihoods, and economic productivity, and expanding access to healthcare and education, especially among disadvantaged groups.

4. Fully fund U.N. humanitarian appeals.

The U.N. is the main coordinator of humanitarian response around the world, but its humanitarian operations are chronically underfunded. Funding for humanitarian needs should include resources to support neighboring countries that host refugees. This is key to protecting countries and even entire regions from destabilization.

5. Provide food assistance quickly and efficiently by increasing the flexibility of U.S. food assistance programs and efforts to facilitate humanitarian access to these populations.

Where food is available and markets are functioning, locally purchased food along with cash vouchers help people get food quickly, avoid disrupting local markets, and save money by reducing shipping costs. Supporting agricultural production, delivery of basic services, stronger infrastructure, and job skills are critical investments to help people get the right nutrition at the right time.

6. Engage in high-level diplomacy to bring opposing parties together, starting with regional peace processes where possible.

In communities where conflict is causing hunger, peace is often the only way to avert hunger crises. The United States often holds influence in conflict-affected regions and can support peace processes. Preference should be given to local or regional solutions to strengthen the capacity of local and regional actors and ensure a durable, lasting peace.

7. Withdraw U.S. military, intelligence, and security support for actors whose actions cut off access to basic needs such as food, medicine, and safe drinking water.

U.S. assistance, including support for development, humanitarian, and military or security support (such as arms sales), should help civilians meet their basic needs. U.S. assistance should not support actions that hinder the well-being of civilian populations.

8. Impose penalties on companies, networks, and officials involved in corruption and crimes in conflict-affected states.

Corrupt actors often purchase weapons, sometimes intended for use against civilians. Penalties for such behavior can deter others from taking similar actions. Responsible engagement imposes those penalties, allowing fragile countries to rebuild and thrive.

9. Bridge humanitarian and development assistance.

Humanitarian aid alone cannot end conflict, nor can it fully respond to the devastating impacts of fragility on individuals, their livelihoods, and national economies. Integrating development efforts into emergency assistance can reduce the risk of recurring crises.

10. Develop long-term and comprehensive strategies of partnership with fragile countries.

All efforts to address humanitarian and development goals should also strengthen the capacity of local systems and institutions, including safety-net programs and governance structures. It takes time to achieve meaningful outcomes. Efforts to sustain peace after conflict, in particular, require long-term approaches.

What is the role of international financial institutions in achieving food security?

We usually think of U.S. development assistance as funding that the United States sends directly to another country. But the United States is also a member of several international financial institutions, usually called IFIs, which can have a profound impact on global hunger. IFIs are important because they are the largest source of international development finance for many countries.

IFIs include, among others, the World Bank, the African Development Bank, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development. The United States and other donors invest funds in these institutions that are then pooled and made available to low- and middle-income countries in the form of grants or low-interest loans, such as through the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA).

When large-scale violence breaks out, the International Monetary Fund notes that “IFIs should remain engaged to prevent the collapse of the state and reduce the economic consequences of conflict. Such institutions can support basic services for the most vulnerable and deploy low-level technical capacity development to keep central banks and payment systems functioning.”

But IFIs also play an important role in policy. “Any policy an IFI enacts in countries marked by conflict and atrocities will send a message about the institution’s level of tolerance for or abhorrence of humanitarian law violations,” says the United States Institute of Peace.

What is Bread for the World doing to address hunger caused by conflict?

Bread members have been leading advocates for robust humanitarian food and nutrition assistance to regions of conflict. Bread has developed a set of guiding principles for hunger advocacy in conflict situations. The principles focus on preventing conflict, providing effective humanitarian responses during conflicts, and engaging in constructive ways to help post-conflict countries rebuild and recover.

Bread is also a member of InterAction, the leading alliance of NGOs and partners in the United States who are serving the world’s most impoverished and vulnerable populations. InterAction monitors and supports its members who respond to global crises, including natural disasters, armed conflicts, man-made famines, and other complex emergencies.

In addition, Bread has advocated for International Development Association (IDA) funding through the World Bank, enabling 75 nations grappling with high rates of hunger and malnutrition to address the humanitarian and developmental requirements of their populations.

Conclusion

It is incumbent upon the United States to do everything in its power, including providing humanitarian assistance, engaging in diplomacy, and putting in place economic policies that will avert the further deepening of the global hunger crisis. As Proverbs 3:27 states, “Do not withhold good from those to whom it is due, when it is in your power to do it” (ESV).

International efforts should focus on seeking a diplomatic resolution to conflict as well as providing immediate assistance. Individuals and communities around the world can be powerful advocates for change – as well as powerful agents of prayer for those impacted by conflict and hunger.