As Bread for the World emphasizes, climate change is one of the main causes of global hunger. People living in parts of the world that are most vulnerable to climate change, who are among the first and most severely impacted, are usually also the least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and have the fewest resources to adapt to it.

Unpredictable weather is only one aspect of climate change, but it produces signs that are hard to miss—ranging from fields with crops that are withered from drought, to stored grains ruined by flooding, to swarms of destructive insects who prefer the new warmer temperatures, to more frequent and intense sudden-onset disasters such as wildfires and hurricanes.

Other types of damage caused by climate change may be less noticeable from a day-to-day vantage point, but they are also devastating. One of these is the growing number of people being forced to leave their homes and farms in search of food and a more viable way of earning a living. Another is the impact of higher carbon dioxide concentration in the soil, with consequences for the nutritional quality of crops. Climate scientists, nutritionists, and other specialists do not yet understand all the implications for human nutrition.

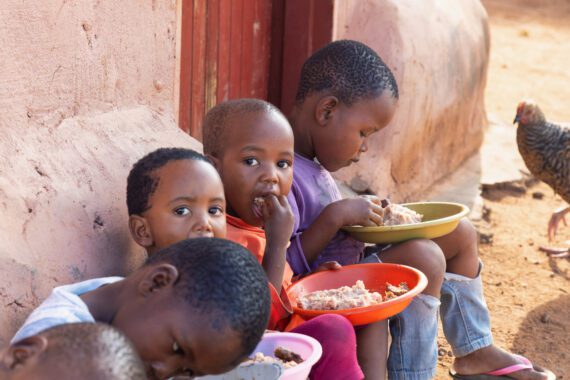

We know, however, that among the people most at risk from malnutrition are two groups that frequently overlap: people who have been displaced either within or outside their home countries; and pregnant women and young children.

According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), for example, disasters linked to climate change can “translate into significant – and negative – nutritional outcomes, including foregone calories and nutrients.”

Researchers at FAO have estimated the potential impact of disasters on the calories available to each person, basing their calculations on data on crop and livestock production loss in least developed, low-income, and middle-income countries between 2008 and 2018. The result was startling—6.9 trillion lost kilocalories per year, or enough calories to feed 7 million adults.

Scientists also worked to calculate the potential loss of specific essential nutrients, including iron, zinc, calcium, Vitamin A, and iodine. The result for loss of nutritional iron, for example, was estimated as enough to meet the needs of 45 million women. Deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals can lead to serious health problems—such as blindness or developmental disabilities— or even death. In fact, iron deficiency anemia is a leading contributor to maternal mortality.

There has been increasing recognition over the past 15 years that the period from pregnancy to a child’s second birthday, often known as the “1,000 Days,” is the most critical window for human nutrition. Malnutrition is the cause of nearly half of all deaths among children under 5, and those who survive malnutrition during the 1,000 Days often suffer permanent damage to their health and development, a condition known as stunting.

Because climate change has led to increasing numbers of babies and toddlers who have been displaced along with their families, it is increasingly important for national governments and the global humanitarian assistance community to identify and implement the most effective ways to protect young children. Groups such as the Infant Feeding in Emergencies (IFE) Core Group promote collaboration among stakeholders seeking to do this.

One effective way of protecting the youngest children during hunger emergencies is continued breastfeeding. According to Colleen Emary, senior technical advisor for nutrition with World Vision, most malnourished mothers will continue to produce breastmilk that meets their babies’ nutritional needs. Milk production will decline only in the most severe cases of malnutrition.

Emary noted that support for breastfeeding is a priority action in the Sphere Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response. “Policy makers, donors, humanitarian responders, community leaders, and crisis-affected communities all have a role to play in ensuring support for breastfeeding mothers in emergencies,” she pointed out.

Supporting breastfeeding includes ensuring that pregnant women and lactating mothers are prioritized for nutritious foods in humanitarian assistance efforts, including post-disaster response. This is more important than ever in the wake of the COVID-19 global pandemic. According to UNICEF, between 2020 and 2022, malnutrition among pregnant and breastfeeding women increased by an estimated 25 percent in 12 of the hardest hit countries.

Michele Learner is managing editor, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.