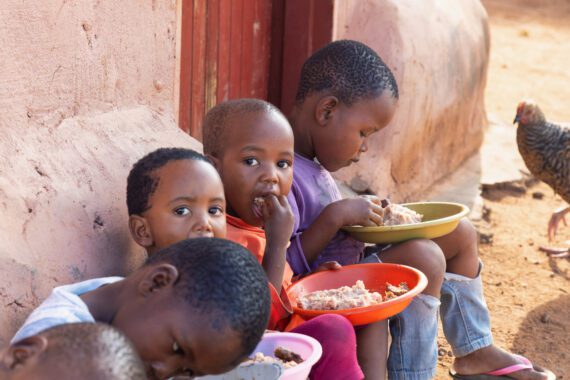

An increasingly widespread and severe global food crisis continues unabated in 2023. Between December 2021 and December 2022, the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance due to acute hunger and malnutrition rose from 274 million to an estimated 340 million.

Through our Hunger Hotspots series, Bread for the World focuses attention on the global hunger and malnutrition crisis—the countries that are most severely affected, the main causes of emergencies, and how we as anti-hunger advocates can help persuade the U.S. government to support the lifesaving assistance that is needed in emergency situations.

Bread notes that in 2022, donor governments around the world allocated record levels of funding to the World Food Programme (WFP), the largest global humanitarian organization. This funding saved lives and helped ensure a healthy future for young children. The problem is that the needs have grown even more.

The United States is critically important to ensuring that emergency humanitarian assistance—food, clean water, and basic medical care—is available to people in need. In fact, in 2022, the U.S. government contributed more than $7.2 billion to the World Food Programme (WFP). That is almost half of WFP’s 2021 budget of $14.8 billion. This significant increase and the innumerable lives saved were possible because Congress recognized the spike in humanitarian needs and approved supplemental funding.

This year, WFP needs to increase its resources. Its plan to supply food for 150 million people carries a cost of about $23 billion. In several countries, providers of WFP emergency assistance have already reported that a shortage of resources has forced them to make decisions that change the lives of millions of desperate people—impossible decisions. Which countries, communities, families, and individual children will have the food they need? Which will receive some food, but not enough? Which must be told—by representatives of humanitarian organizations whose mission is to save lives—that there is not enough to go around, that the international community cannot help them?

The agency, led since early April 2023 by new executive director Cindy McCain, reduced staff and operating costs as its first effort to make ends meet. But soaring global needs, combined with inflation, more than offset the cost savings these measures achieved. In every world region, WFP has had to cut its distribution of food and money to buy food. Each month, some groups in the population of people in need are given smaller rations than the month before, while still others must be notified that they are no longer eligible for assistance.

WFP is almost completely reliant on funding from donor governments, but it is working to diversify its funding sources. Potential contributors include wealthy nations that are not yet donors, regional nongovernmental organizations, the private sector, individuals in donor countries, and the governments of countries newer to supporting humanitarian assistance. For example, a May 2023 High-Level Pledging Event on the Humanitarian Response in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia included pledges from regional organizations such as Islamic Relief and the governments of South Korea and the Czech Republic.

Bread for the World emphasizes that emergency assistance is essential but not enough to end hunger. Resolving the root causes—for example, armed conflict or gender inequities—must be a priority as well. WFP executive director Cindy McCain said, “If we can prepare at-risk communities to handle future climate shocks, they won’t need emergency support the next time there’s a drought or flood.”

Recent examples show that initiatives that enable people to prepare in advance are effective. In 2022, Niger was in its worst hunger crisis in 10 years. But because WFP had previously implemented programs to build resilience in some of the hardest-hit areas, 80 percent of the villages in highly affected areas did not require humanitarian assistance.

Michele Learner is managing editor, Policy and Research Institute, with Bread for the World.