Editor’s note: Bread’s 2016 Offering of Letters: Survive and Thrive focuses on the nutrition of mothers and children in developing countries. Sometimes, however, it’s challenging for Americans to understand the connection between the letters they write to Congress and what happens on the ground in far-away places in the work of ending hunger.

To better understand the connection, Bread is partnering with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to post USAID stories on Bread Blog. This story first appeared on the organization’s website.

By Lindsey Spanner

Before last year’s harvest, most people living in the northern region of Ghana had never seen an orange-fleshed sweet potato. Now, this brightly colored vegetable may be on its way to becoming the region’s most popular crop.

This variety of potato was recently introduced to communities in Northern Ghana through a USAID project to counter Vitamin A deficiency — a condition that compromises the immune system and can lead to blindness. Last year, 439 women in 17 districts learned how to cultivate orange-fleshed sweet potatoes for the first time.

The villagers lovingly call the new crop “Alafie Wuljo,” which means “healthy potato” in the local language of Dagbani. At one community’s first harvest celebration, the head of the project Philippe LeMay recalls how government officials and community leaders came to learn how to use the new crop in the kitchen.

There were several cooking demonstrations, but the sweet potato fries were a hit among schoolchildren. “Now everyone wants to grow orange-fleshed sweet potatoes,” said LeMay.

But encouraging farmers to plant nutritious crops is just one of several strategies employed by this project to address malnutrition in northern Ghana. Besides agriculture, we are also working on improving livelihoods; governance; nutrition; and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). These sectors are interrelated and help to achieve common goals.

The project introduces new and more nutritious crops to farmers and helps them boost yields through improved farming techniques. It also links farmers to markets, helps community members create village savings and loans associations, works to improve water and sanitation infrastructure, and promotes better hygiene.

Ghana is one of the first countries to put USAID’s Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy into action. The fresh approach, which will guide our work through 2025, cuts across several development areas, resulting in programs that are more cost-effective and deliver greater impact around the world.

The strength of USAID programs in more than 100 countries provides a large delivery platform for scaling up nutrition services. Just scaling up nutrition-specific interventions to 90 percent coverage will generate a ratio in which every dollar invested yields a $16 rate of return.

At a regional Global Learning and Evidence Exchange workshop in Accra, Ghana last month, project representatives shared their experiences, explaining how they overcame the challenges of coordinating across different development sectors. In some countries, technical offices such as agriculture, nutrition and WASH aren’t used to working together. LeMay thinks the transition went smoothly in Ghana in part because the various technical offices are housed within the same government structure.

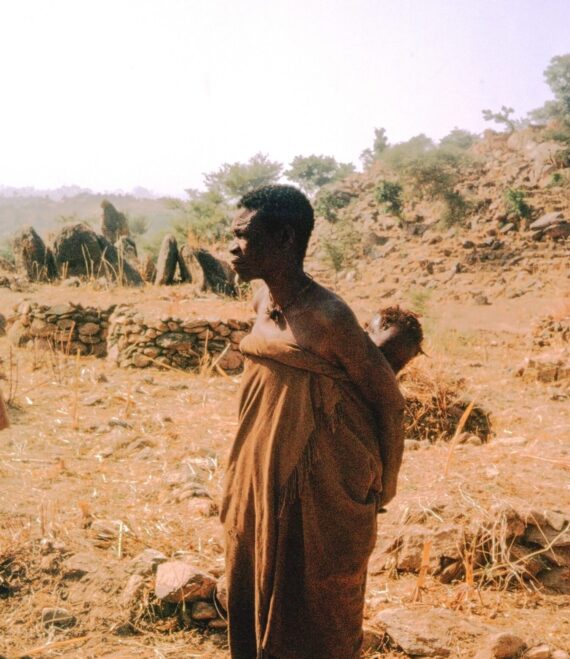

The northern region of Ghana has developed at a much slower pace than the rest of the country because of its remote location, limited resources, sparse population and inhospitable climate. More than a third of children under 5 in these districts suffer from stunted growth, a result of poor nutrition.